About this page

This page is a digital version of the book Kolomyya Forever, by Ariah Suchman (author) and Michael Toben (English language editor). Suchman copyrighted the book, but as he has since passed away, and it seems to be impossible to obtain a physical copy of it, I feel sure that he would rather it be available than not. (The book makes clear in several places, e.g. page 7, that it is intended as a memorial.)

I have tried to faithfully reproduce the text of the physical book, even including page numbers, typos, and so on (though I'm sure that I introduced some typos of my own). Anything you see in green boxes (like this one) is not part of the physical book, but everything else is.

I apologize for my low-quality reproductions of the photographs, maps, and drawings in the book. (They're from pictures I took with a camera, so are a bit distorted, and some are a bit brownish depending on lighting.)

As you'll quickly see, this page is still a work in progress. Last update: 2023-01-18.

About Kolomyya Forever

Kolomyya Forever is the English title of קולומיה לנצח by Ariah Suchman (אריה סוכמן). Some links about the book:

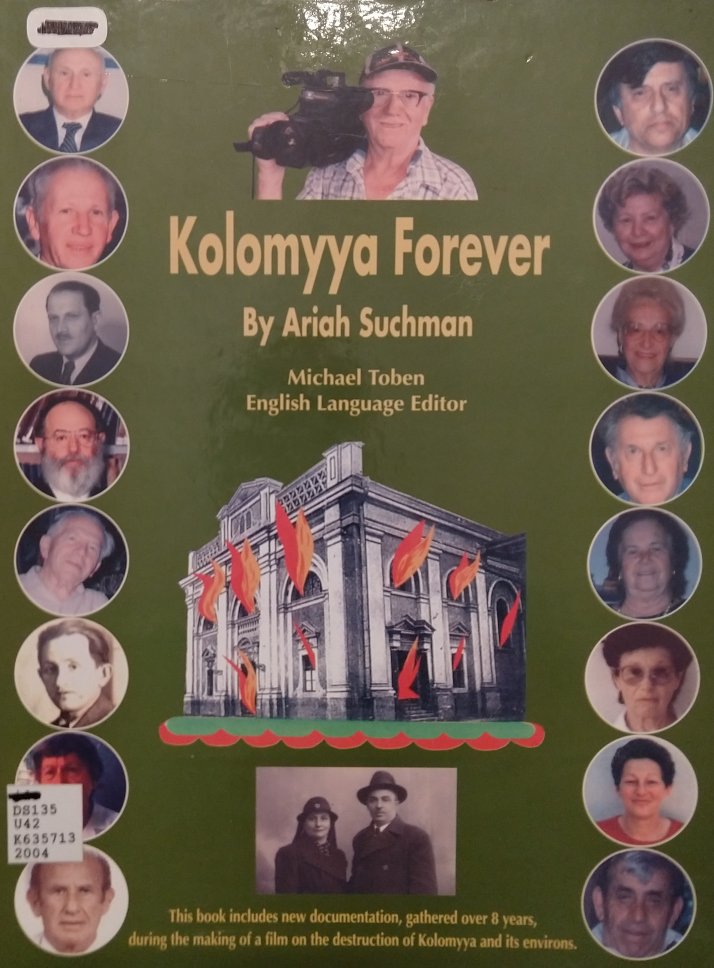

front

cover

p. 1

Kolomyya Forever

Arie Suchman

English Language Editor

This book includes new documentation, gathered over 8 years, during the making of a film on the destruction of Kolomyya and its environs.

p. 2

5764 / 2004

All rights reserved by the author.

p. 3

Table of Contents

- 9 In Memoriam

- 10 Preface

- 11 TODO Acknowledgments

- 16 Introduction

- 17 Forward from the production assistant

- 18 A film commemorating the Jews of Kolomyya

- 22 TODO Letters from distinguished personalities and institutions

- 27 ‘Prager Center’ Museum

- 29 Maps of Poland 1939-1945

- 32 Kolomyya

- 33 The author’s mother and Emperor Franz Josef in Kolomyya

- 34 Map of the Austro-Hungarian Empire

- 36 Pictures from Kolomyya

- 38 Yitzhak Teitlebaum

- 40 Edward Firestone

- 43 Yaakov Kube Menashes

- 44 TODO Rabbi David from Kilomyya reveals the greatness of the Baal Shem Tov

- 54 Beautiful pastoral scene of the Carpathian mountains

- 55 Rabbi Lau uprooted the tombstones

- 61 Photographs of Kolomyya

- 70 Documenting the Holocaust

- 73 The film: The Jews of Kolomyya

- 75 A brief history of Poland and Galicia

- 79 Outbreak of the war between Germany and the Soviet Union

- 83 The Nazi German and Soviet Union pact

- 85 Order of the Day of the Nazi Army on the eve of its invasion of Poland

- 86 General Governor Hans Frank

- p. 4

- 87 War breaks out between Communist Russia and Nazi Germany

- 90 In Recognition by Bhira Zakai

- 91 A visit to my city Kolomyya

- 93 Testimony of the holocaust survivor from Kolomyya, Edit (Icia) Glasberg

- 98 To Professor Maria Rosenbloom

- 99 An interview with Professor Maria Rosenbloom

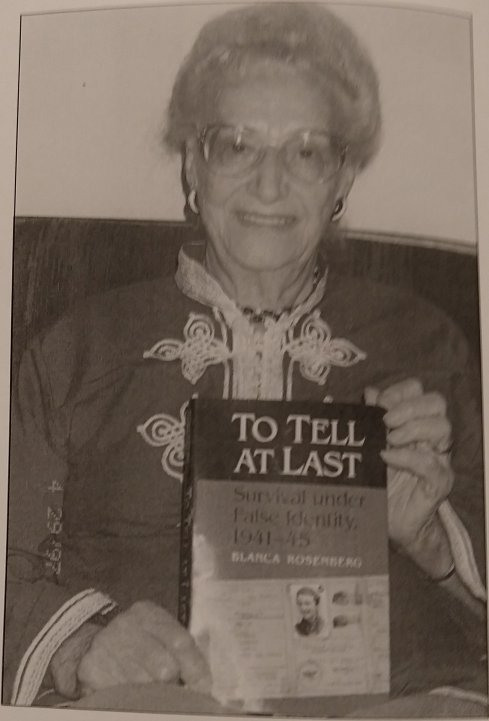

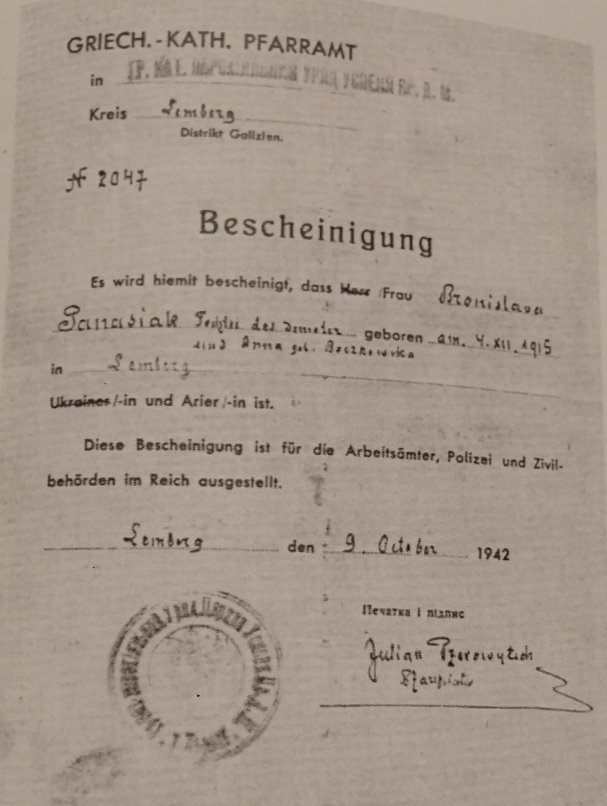

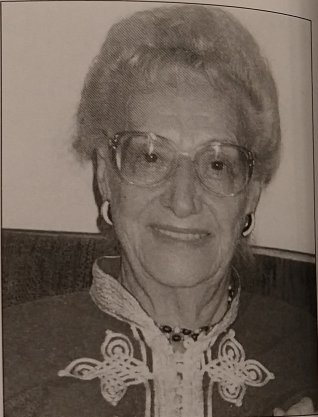

- 107 Professor Blanca Rosenberg z’l

- 110 To Tell at Last

- 113 An interview with Professor Blanca Rosenberg

- 121 Chedva Kaufman

- 126 The testimony of a holocaust survivor, Mr Yaakov Zinger

- 130 The establishment of the Ghetto

- 139 Mordecahi Horwitz, Chairman of the Judenrat in Kolomyya

- 140 The railroad station in Kolomyya

- 141 Avraham Taub - hero of the Death Train

- 143 The testimony of Moshe Bretter

- 144 Kolomyya under the Nazis

- 146 An aktion in the ghetto

- 148 TODO Jews of the Ghettos

- 152 Professor Menek Goldstein z’l

- 153 The last day in the ghetto of Kolomyya

- 156 TODO Memorial Service Tribute to Menek Goldstein

- 163 The testimony of Salomon and Miriam Gutman

- 170 The testimony of Yeshayahu Likvornik

- 174 Righteous Gentiles - Vasilian and his sister Anya Petrovski

- 178 Dates of the aktions that took place in Kolomyya

- 179 TODO General Botschkivki, National hero of the Red Army

- 180 TODO Photos of the cemetery of the fallen of the Red Army in Kolomyya and the Monument to the Jewish soldiers from Kolomyya

- p. 5

- 181 TODO Order of the Supreme Command

- 182 TODO The liberation of Kolomyya from the Fascists

- 183 TODO May 9 is Victory Day over the German Nazis and a day of heroism

- 184 TODO Photographs taken during the bloody battles

- 186 TODO The capture of the Austrian war criminals

- 187 TODO Nazi Criminals slaughtered 80 thousand Jews from Kolomyya, Murders of Kolomyya Jews return to Vienna

- 188 TODO Chronicles of Nazi war criminals after the Second World War

- 190 TODO The dark secret of a noble-spirited journalist

- 193 TODO What was your business in Kolomyya?

- 196 TODO Deliverance

- 201 TODO Belzec Death Camp

- 204 TODO A translation of the inscription on the commemorative plaque in the Belzec camp

- 205 TODO The commemorative plaque at the Belzec extermination camp

- 207 TODO Kaddish in Belzec

- 208 TODO Phorographs of the Belzec camp - signs, monuments, etc.

- 210 TODO The remains of the Belzec camp

- 211 TODO A memorial ceremony held in the Shoporovtze forest

- 213 TODO Speeches made at the ceremny held at the Shoporovtze (Shoporvtza) Forest Memorial

- 216 TODO The burial of the ashes of the martyrs of Kolomyya

- 219 TODO Hanan Weisman

- 222 TODO Jacob Kuba Muntskik, z’l

- 223 TODO In the spirit of the 9th of Av

- 224 TODO I the name of the victims

- 225 TODO In memory of the martyrs

- 226 Yizkor

p. 6

This book has been published

with the assistance of:

Yad Veshem,

The Authority

for Memorializing the Holocaust and Martyrdom.

The

Foundation for Supporting Memorial Books of Holocaust Survivors,

The Azrieli Mall Chain, Azrieli Center, and IC of the Azrieli Group,

Thanks are also due to the Amos Foundation of the

President's Office for their generous contribution.

p. 7

Praise the Lord of the Universe who installed in the hearts of man the spirit of generosity and helped me to complete this memorial to the Jews of Kolomyya and its environs.

p. 8

This book is a companion work to two films, Kolomyya during the Holocaust and Vasilian and his sister, Righteous Gentiles which deal with the destruction of Jewish Kolomyya and its environs during the Holocaust.

For the future generations, the book and the films will be a permanent memorial to the memory of the Jews of Kolomyya and its environs who perished in the Holocaust.

p. 9

IN MEMORIAM

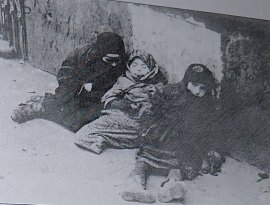

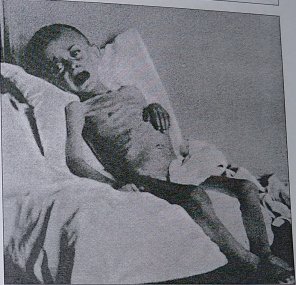

To the memory of the Jews of Kolomyya and its environs,

Eighty thousand martyrs, men, women, children,

Murdered in the Holocaust by the Nazis, may their name be blotted out.

May the souls of the martyrs be counted among the living.

May God revenge their murder.

Let us remember the young people of Kolomyya and its environs

who fought heroically against the Nazis

in the ranks of the Soviet Army and the Polish Army

and who fell in battle and whose burial place is unknown.

May the Lord avenge their blood.

To the memory of the souls of the members of my family

Who were murdered in Kolomyya

And in the death camp of Bergen Belsen,

My maternal grandfather, Yaakov Wasserman

And my maternal uncles, Kassiel Yager, his wife and children,

Itzik Yager, his wife and children

Benjamin Yager, his wife and children, from the town of Tchernovitz.

My mother's sister, Ester-Rachel bat Yaakov,

Her husband and their two sons from Tchernovitz,

My mother's two brothers from Kolomyya,

Yehuda Meshel, his wife and their daughter, Elka,

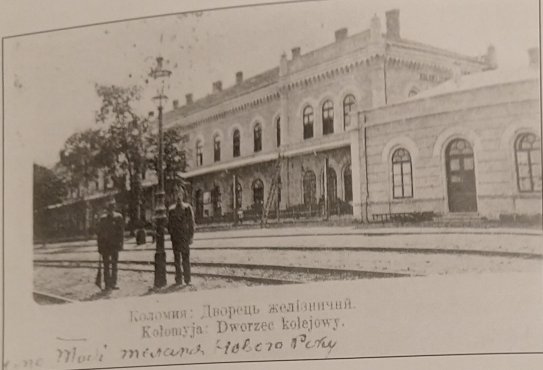

And Yoseph Leib, his wife and their children,

And all the rest of the members of my family whose names I no longer recall.

May their memories be blessed.

May God revenge their deaths.

p. 10

Preface

Ariah Suchman,

author of Kolomyya Forever

Many memorial books have been written to commemorate Jewish communities which were destroyed in the Holocaust, and among them the books on Kolomyya Jewry: Pinkas Kolomyya, (Kolomyya Notebook) in Yiddish and Yizkor K'hilat Kolomyya (Remember the Kolomyya Community) in Hebrew. No doubt all that has been written is a mere drop in the ocean compared to all that could have been written about each and every Jew who survived the Holocaust, and about those who were tragically murdered in the Holocaust.

Many of the horrors of those days have not yet been described or memorialized in a book. Now, fifty-five years after the war's end, there are fewer and fewer people left who remember the horrifying events of those days.

Eight years ago, I felt the need to perform a more concrete act of memorializing. I felt the need to make a documentary film which would be a living testimony, bringing alive the horrors of the Holocaust for the viewer.

In our generation, when television and the visual media have captured the masses, and people want to view historical events with their own eyes — more than to read about them in a book - a documentary film is actually the testimony which most effectively brings the horrors of the Holocaust alive for the viewer.

I approached the production of this documentary film from the depths of my memory, and with a sense of heavy responsibility and solidarity with the martyrs. For more than seven years, I faced many challenges including the need to collect documentary materials, especially from Kolomyya and its environs, to film documentary footage at the sites of the destruction and the old Ghetto, to write the script, to edit and proofread the narration, to film and record interviews with survivors, and to work on continuity in the film studio The result is an hour-long film. The viewer may not understand what is involved in the details of the production of a documentary film, but it is a difficult and arduous task.

Such a production is also quite costly — tens of thousands of dollars - which I did not have. I trusted that God would move the hearts of the people from Kolomyya to contribute towards its production. The help I received from my assistant, Ephraim Arbel, was nothing short of a miracle. We spent many days and nights working on the film. In both our names, I would like to thank the survivors of the Kolomyya Ghetto, now living in Israel and abroad, who graciously agreed to be interviewed for the film.

Finally, after the film was completed, I decided that it would need a book to accompany it. After much effort and a number of years, this is the product. My thanks go out to the innumerable people who contributed in so many ways to make this book possible.

p. 11

p. 12

p. 13

p. 14

p. 15

Acknowledgements

TODO: type up the acknowledgements (pages 11 through 15)

The goal of this book is to perpetuate the memory of the Jews of Kolomyya and the environs, and is not for any financial profit.

p. 16

Introduction

The book Kolomyya Forever is a memorial to those who were killed and butchered in the Kolomyya Ghetto. The book describes the terrible and horrifying experiences of the ghetto residents from september 1941, until their final liquidation in March 1943.

The book presents ten complete testimonies of those who survived the inferno. Three of the survivors emigrated to the United States after the war, and subsequently gained a reputation in the academic world. Their live testimony can be seen in the film "The Jews of Kolomyya during the Holocaust".

In those years of darkness and shadow there were also those, however few, who did not lose their humanity and who, at great risk to themselves, seved Jews from their killers. Vasilian Petrovski and his sister Anya are examples of such people. They endangered their lives by hiding sixteen Jews in their house, which was one hundred meters away from the Gestapo headquarters. On 12.11.97, Yad Vashem awarded them the title of 'Righteous gentiles'. The heroism and courage of these two people are described at length in the book by the survivors. The book preserves the memory of these events in documents and testimonies of the survivors. The book records the award ceremony that was held in the Garden of the Righteous Gentiles in Yad Vashem, Jerusalem.

The book, Kolomyya Forever and the two accompanying films are the products of many years of work. This trilogy tries to five as accurate a picture as possible of what happened to the community of Kolomyya during the terrible years of the Holocaust in Europe. The fate of this community with its very personal stories is the same fate of the rest of the European Jewish communities in this period, except for some details.

The book is intended as a study source and reference for high school pupils and students, and for all who are interested in the history of the Jewish people. I pray that this contribution of mine will help to make the youth of our nation become more aware of the importance of the study of the Holocaust heritage. In addition, the films and book will also contribute in the struglle against those who deny the Holocaust.

Ariah Suchman

p. 17

Our thanks to Mr. Ephraim Arbel

Efraim Arbel

Our deep thanks to my friend Ephraim Arbel for his extended help in the production of the film on the Holocaust of the Jews of Kolomyya and its environs. Together we carried the burden and handled all the difficulties in applying to various institutes for aid in making the film. Unfortunately, we often suffered disappointments.

I thank you for your hard work and we are all greatly indebted to you for your contribution and I wish you every success and may God bless you.

Your friend,

Ariah Suchman

Producer

From the film production assistant

I first met Ariah Suchman in the framework of cultural and educational work in the Dovev-Oz community in Ramat Gan. He told me about the work of perpetuating the memory he had been engaged in already for several years, namely, the production of a documentary film to perpetuate the memory of the Jews of Kolomyya who were murdered in the Holocaust. I expressed interest in the subject and then Ariah contacted me and asked me to be his production assistant.

The work in the project was very complicated. It was very difficult to obtain photographic documentary material of Kolomyya and the environs. Ariah ran from place to place and made contact with survivors from the Kolomyya Ghetto in Israel and abroad in order to interview them for the film, as well as to find sponsors for the project. He also made contact with people in Kolomyya in order that they should send him photographic material from there.

For many years, night and day, we engaged in editing, working in the film studio. During all this time Ariah tried to obtain financial support from institutions in Israel and more than once was sent away empty-handed. It was painstaking work over the years.

Thanks to his great and untiring dedication, and above all by the grace of the Lord, we managed to complete the documentary film commemorating the memory of the Jews of Kolomyya and its environs.

Ephraim Arbel

Assistant to the producer of the film

p. 18

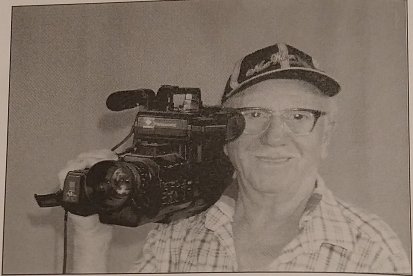

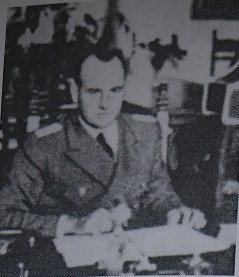

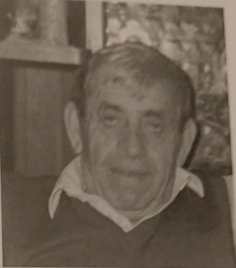

Ariah Suchman, Ariah Suchman, producer and director of the film The Jews

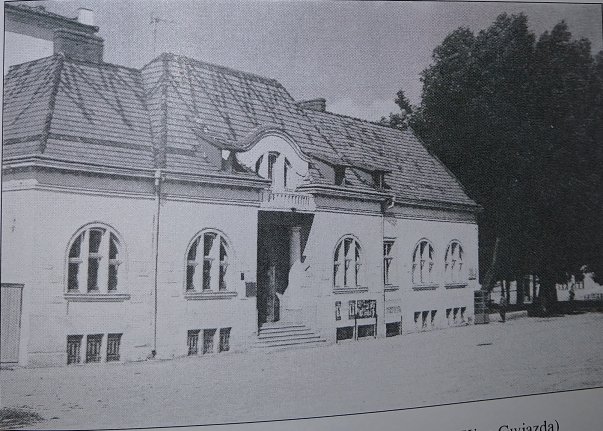

of Kolomyya.

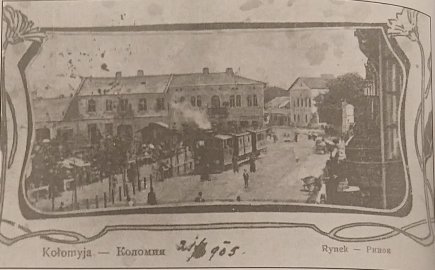

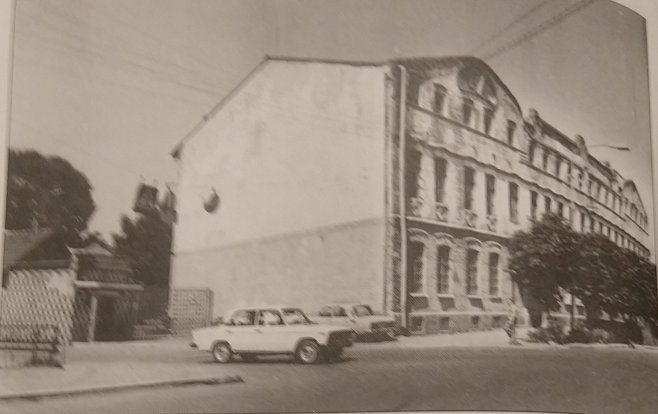

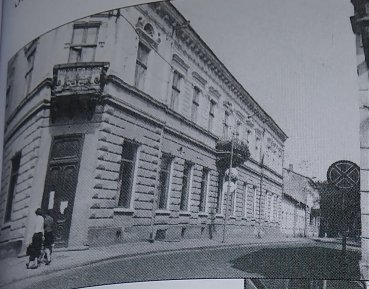

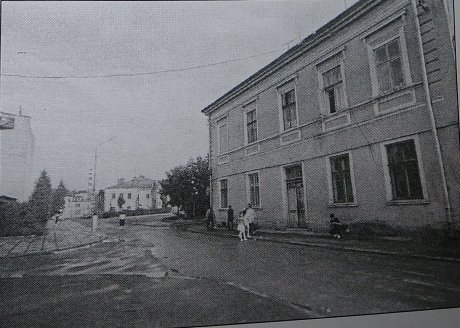

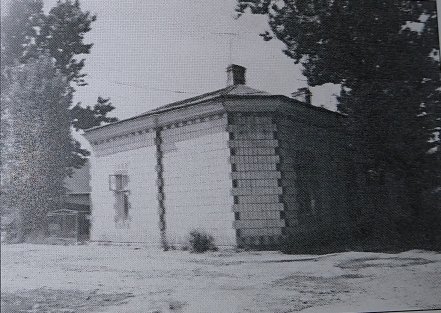

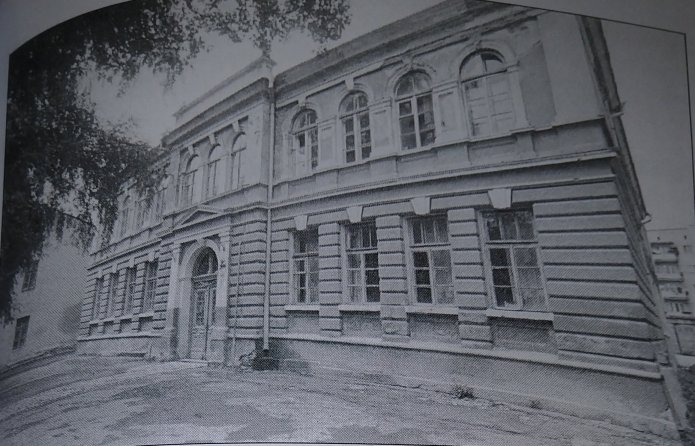

The Savings Bank and the National Theatre in Kolomyya

p. 19

On the occasion of the first showing of the film The Jews of

Kolomyya

Above left: the Chief Rabbi of Israel, Rabbi Meir Lau who spoke at the

ceremony.

Above right: Rabbi Yechiel Wasserman, deputy mayor of Givatayim, opening the

event.

Bottom: Rabbi Skolsky, Director of the Kiddush Hashem Archive and his team of

assistants

p. 20

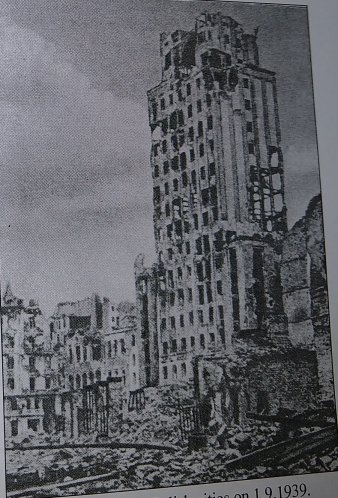

The city of Kolomea after its liberation

The city square at the center of Kolomyya

p. 21

The film The Jews of Kolomyya was screened at Bet Wohlin on

3.2.1999 on the 55th anniversary of the cessation of the extermination of the

Jews of Kolomyya and its environs. The banner reads,

"City of Givatayim — A film in memory of Kolomyya Jewry during the

Holocaust will be shown under the auspices of the mayor, Efi Stenzler —

Beit Wohlin, Wednesday 02/03/1999 at 4:00 PM".

Members of the audience at the premiere screening of the documentary The

Jews of Kolomyya.

p. 22

בס״ד

Israel Meir Lau

Chief Rabbi

of Israel

President of The Great Rabbinical Court

25 Tammuz 5761

16 July, 2001

Mr. Ariah Suchman,

Ramat Gan

Dear Mr. Suchman,

I was pleased to hear that you have devoted great efforts to memorialize the community of Kolomyya both in a film and in a wide-ranging book.

TODO: type the rest of this letter

With sincere greetings,

Israel Meir Lau

Chief Rabbi of

Israel

p. 23

A Translation of a letter sent on 29.7.1997 by Yad Vashem, Tel-Aviv area.

Mr Ariah Suchman

Producer of The Jews of Kolomyya

Ramat Gam

Dear Sirs:

TODO: type the rest of this letter, and attach the photograph of Avigdor Efron

p. 24

My sincere blessings to you, Mr. Suchman. May there be many more like you.

Respectfully,

Avigdor Efron

Director of the Educational

Center for the Holocaust

Yad Vashem, Tel Aviv District

p. 25

אוניברסיטת תל-אביב

TEL AVIV UNIVERSITY

The Lester and Sally Entin Faculty of Humanities

The Stephen Roth Institute for the Study of Contemporary Anti-Semitism

and Racism

16.7.99

Dear Mr. Suchman,

TODO: type the rest of this letter

Sincerely,

Dr. Ronny Shtauber,

Coordinator of the

Foundation

for the Study of Anti-Semitism

p. 26

Letter from Rabbi David Skolski (Kidush Hashem Archives)

Re: The Hebrew book Kolomyya Forever

TODO: type the rest of this letter, and attach the photograph of Rabbi David Skosky

Very sincerely,

Rabbi David Skolski

Director

p. 27

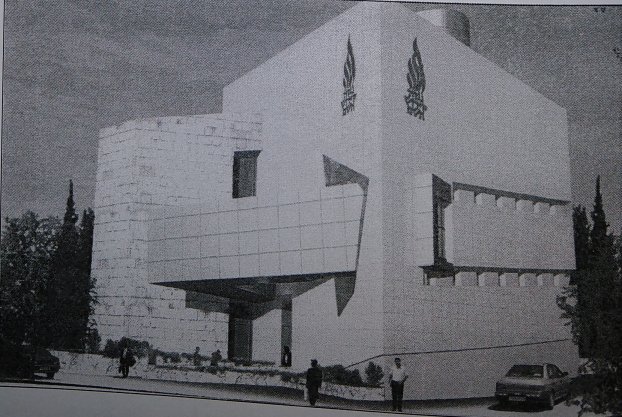

"Prager Center" Museum - Ganzach Kiddush Hashem

The splendor of the Jewish Nation, the charm of its holidays, the multifaceted nature of its daily conduct, the myriad‘s of charitable and mutual-assistance with which it was blessed - were at all times the focus of attraction to those who benefited from this exemplary behavior, as well as a source of envy to the non-Jewish world.

The Jewish nation in all its dispersions has managed to maintain its uniqueness. The two thousand years of Diaspora during which it wandered all over the world, battered and weakened by crusades, persecuted and exiled by the Spanish Inquisition, harassed and decimated by all kinds of pogroms - did not succeed in demolishing its spirit and to shake its allegiance to its Jewish heritage.

Our generation, a generation of hardship and wonders, has felt on its body the collapse of the Jewish world when the horrible Holocaust was inflicted on it by Nazi beast, and had the merit to witness the revival of the Jewish nation and the reincarnation of the “eternal Jew“ that sinks his roots increasingly deeper into the soil.

The researcher and published author, Mr. Moshe Prager, O.B.M., the Founder of “Kidush Hashem Archives - Memorial Center for Research and Documentation“, has lived to see three worlds:

He saw European Jewry during its heyday, during the time when millions of its sons continued to flourish on a soil where they and their predecessors sunk roots during two millennia; he has lived through and seen the horror of the Holocaust when this Jewry has been robbed of its beauty and magnificence, and he lived to see, observe and contemplate the rise of a new mangificent generation from the ashes of the crematoria.

He has felt and obligation to serve as the "connecting link" that has remained alive in order to join and unite the pats with the present and future generations and to transmit to them their glorious heritage.

The Goals

- Our institution - "Kidush Hashem Archives - Memorial Center for Research and Documentation", was established by Mr. Prager in 1963 in order to preserve the wealth of testimony on the spiritual bravery of Jews during the Holocaust and on the miracle of the rising of the Jewish nation from the ashes of crematoria and to give access to them to the public. He did this in order to attain several clearly defined goals, the implementation of which took up all his time and energy:

- To investigate, collect and record for posterity all the manifestations of Jewish spiritual heroism in our generation, when the Nazi fiend contrived to annihilate the nation that proclaimed the belief in the Almighty in the world. The Jew, unshaken in his faith, defended it against all odds and refused to repudiate it under the most trying circumstances. The same Jew, who was persecuted by p. 28 bloodthirsty Arabs in the East and by Communists in the Soviet Union, has spiritually survived, and under these circumstances his survival serves as irrefutable and persuasive evidence that all the Jews of the world are one Nation, whose spiritual heritage is indestructible.

- To salvage all forms of recorded documentation that manifest the unique image of the Jew throughout history and the entire spectrum of life styles of the Jewish world that is no longer. This is a dual goal: it is intended both to commemorate the glory of the Jewish nation and to awaken and foster the effort to re-forge the chain of generations and to build the life of the Jewish Nation on the foundation of the Jewish heritage.

- This goal combines the two previous goals and consists in establishing a museum, the exhibits of which would illustrate to the new generation, new immigrants and tourists from the entire world the manifestations of Jewish spiritual heroism under the Nazi occupation, the mutual assistance extended under the most trying circumstances and the brave resistance to the suppression of the spirit under the most horrendous conditions in recorded history. All this would be done with the purpose of the museum serving as a means to educate the younger generation by bringing them closer to their glorious past and imbuing them with true Jewish pride.

To attain all these goals, Moshe Prager started collecting documents and photographs from many sources. He traveled extensively abroad and went through all the many private and public archives, an enterprise that required unlimited patience and effort.

The Prager Center Museum - Kiddush Hashem Archives

p. 29

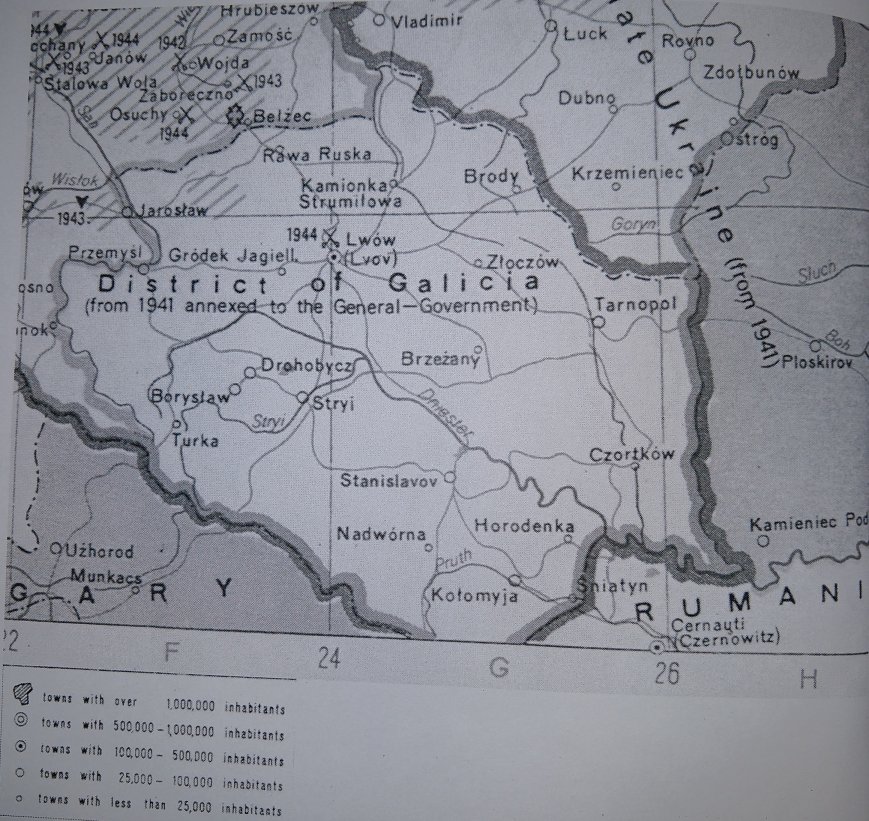

The partition of Poland between Germany and the Soviet Union,

28

September 1939

p. 30

Map of east Galicia during the Nazi occupation — 1941

p. 31

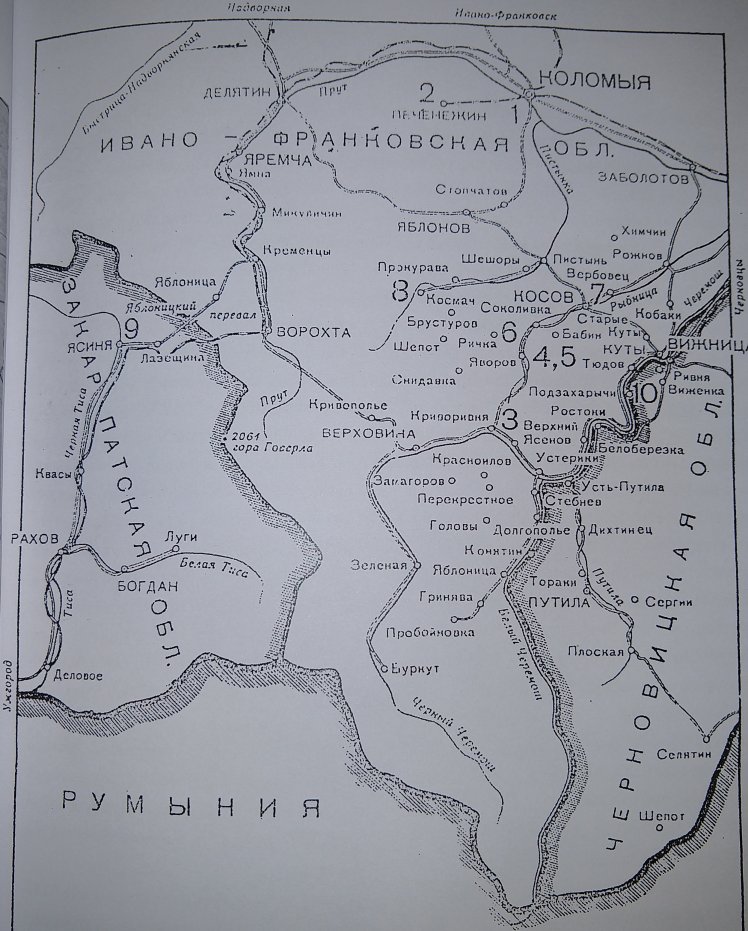

The regional map of Kolomyya and its environs including its southern and

eastern borders. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the area came

under the jurisdiction of the Ukraine. Kolomyya is in

the upper-right-hand (northeast) corner of the map, labeled in Russian as

"КОЛОМЫЯ".

p. 32

Kolomyya

The city of Kolomyya today is part of the Ukraine, standing on the banks of the River Prot. Before the Second World War it was in the southeast area of Poland, that is eastern Galicia. Not too far south is Romania , in the northwest is Poland, to the southwest stand the Carpathian Mountains.

According to archaeological findings and official accounts, the city of Kolomyya is one of the earliest settlements in Galicia. The first official date is 1241, though archaeologists claim that it dates much further back. In its beginnings, Kolomyya was a military fort that protected the southwest border of ancient Russia. The city underwent several changes. In 1259, the fortresses were destroyed, evidently by Prince Daniel of Galicia under the command of the Mongol-Tets. In the middle of the 14th century, Galicia was conquered by the Poles and was constantly under threat of foreign invasion. According to Polish accounts the city was burned by the Tets in 1621 and its inhabitants annihilated. In time, the city was rebuilt and it was situated on the commercial route from Poland and Germany through Galicia to Volga and the Danube: to Kiev and to Hungary and Czechoslovakia. After the first division of Poland in 1772, Kolomyya was annexed to Austria. The Levov-Chernovitz railroad was built in 1866, and the line between Levov and Bucharest was built in 1876, and contributed to the fast development of the city. After the First World War it was under Nazi rule for about three years. In 1944 it was liberated and annexed by the Soviet Union. With the fall of the Soviet Union it has become part of the Ukraine.

A number of Jews settled in Kolomyya and its surroundings at the beginning of the 16th century. There is evidence that Jews lived there even earlier. In time, the Jewish population grew. Before 1914, Kolomyya had 41,000 inhabitants with more than half of them Jews. In the First World War many Jews left and not all of them returned. The Jews in Kolomyya were active in commerce, industry and craftsmanship. The industry of building materials, such as bricks, was also in the hands of the Jews. Before World War One Kolomyya was an important military center of the Austrian empire and the Jews made their living from work for the military.

Kolomyya is known as a Chassidic city. The Baal Shem Tov also worked in Kolomyya and legend has it that he was born in a suburb of Kolomyya, Okop. The Chassidic movement spread to many areas and many rabbis came to Kolomyya. Even with the spread of higher education and secularism, Kolomyya did not lose its Chassidic character. It should be noted that in Kolomyya there was no widening of the gaps between the Chassidic movements and the other Jewish movements.

Emperor Franz Joseph enjoyed a long reign of fifty-eight years over the Austrian empire. From 1848 until 1916 he was engaged in various wars with national minorities who wished to establish independent states. In the latter part of his reign, the First World War took place, and in 1916 he died in the middle of the war, deeply depressed.

Franz Joseph was much admired by the Jews since he acted tolerantly towards them and extended his protection to them; as a result he was highly regarded as a ruler who protected the Jews. There were two p. 33 million Jews in his kingdom who were loyal to their benefactor. During the First World War thousands of them served in the army and many fell in the battles. Among those taken prisoner by the Russians was my father, Tzvi Suchman z’l, and my uncle Josef Leib z’l.

It should be noted that in all the synagogues throughout Eastern Galicia prayers were recited in Hebrew, Yiddish or German for the well being of the Emperor, which blessed the Emperor with the words: “To the Emperor Ephraim Joseph, May you be blessed and successful for one hundred and twenty years.”

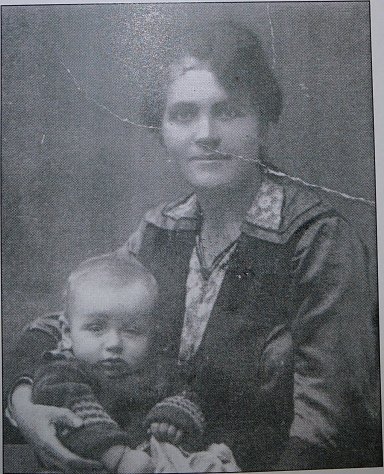

The author’s mother and Emperor Franz Joseph

My mother, Tehila z’l, told me of an interesting event. When she was about 12, she was in a group of some ten girls chosen to welcome the Emperor Franz Joseph when he came to visit Kolomyya.

When the Emperor arrived in the center of the town towards noon, big crowds were waiting to see him. The town rabbis came out to meet him carrying Torah scrolls. They stationed themselves on the left and the church clergy stood on the right carrying crosses. When the Emperor descended from his carriage he approached the group of girls to taste the bread that the town’s girls offered him. Then he went and kissed the Torah scrolls, and only after that did he turn to the priests and kissed the crosses. Such was the esteem in which the Emperor held the Jews.

Ariah Suchman

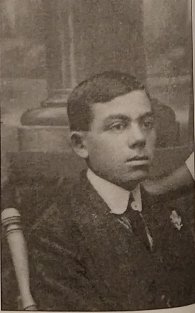

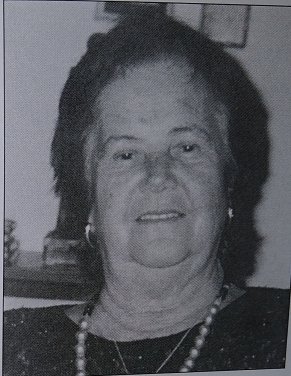

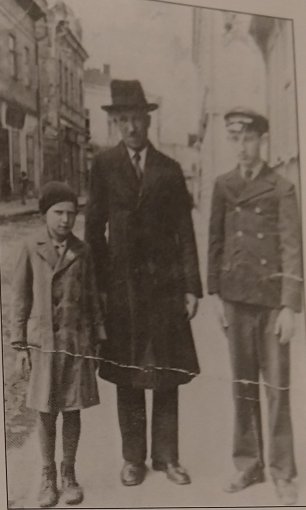

Photograph of the author’s mother Tehila Suchman z’l, neé Yaakov

Wasserman, with her eldest son, Moshe. The photograph was taken during the First

World War in Vienna.

p. 34

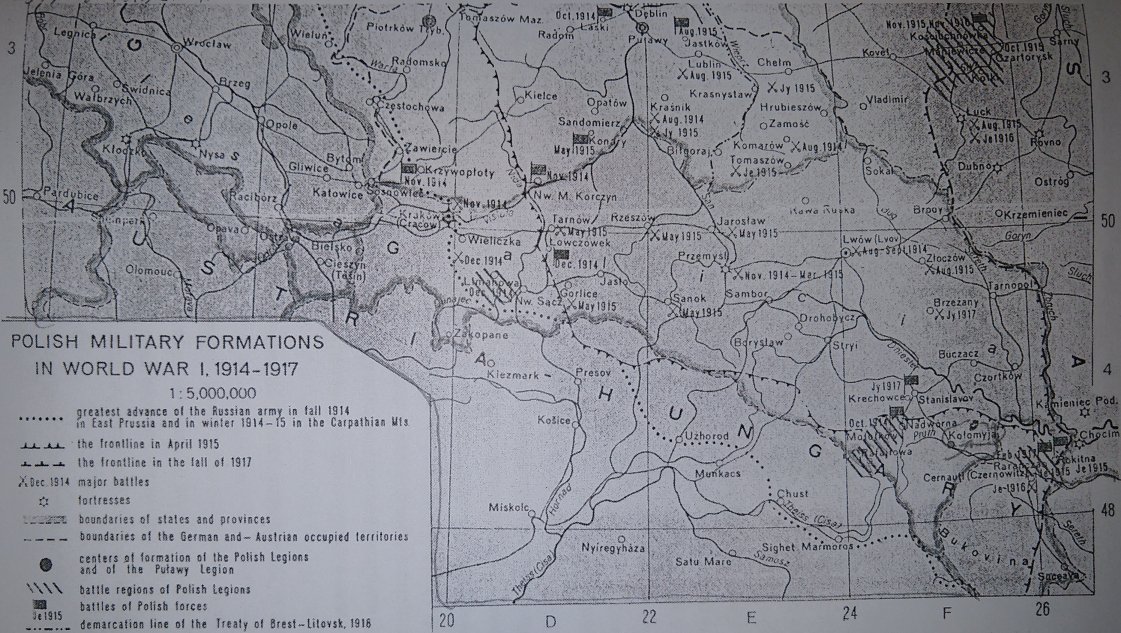

Map of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, eastern Galicia and Bukovina until the outbreak of the First World War

p. 35

Kolomyya in the Modern Period

Kolomyya excelled in Zionist pioneer activities. The first Zionists that were active there at the end of the 19th century were Dr Natan Birnbaum and Rabbi Ariah Laibel Toibash. Many pioneers who settled in Eretz Israel came from these pioneer movements that were operating before the Holocaust.

Among the many Jews who became famous for their economic activities in Kolomyya were two families in particular, the Brettler family and the Horowitz family.

Between the two world wars there were 35 Jewish doctors in Kolomyya (as opposed to 11 Christian doctors) and 45 lawyers, many of them highly regarded. There were also professors who taught at the Jewish Gymnasia and in other schools. It should be mentioned that a number of the doctors and academics were women.

The last chief rabbi of Kolomyya was the Rabbi Yosef Lau, a rabbi beloved by both the Jewish and non-Jewish community alike, a man who gave his soul for the Jews of Kolomyya and was murdered by the Nazis along with many other Jews from the city.

The city of Kolomyya, which was renowned for its Jewish character, was destroyed in the heinous Holocaust, but the memory of the Jews that died with the Name of the Lord on their lips will never be forgotten.

p. 36

Emperor Franz Joseph

'HaLokleka', the first train to arrive at the center of the city during

the time of the Austrians

The center of Kolomyya during the Austrian rule, 1917-18

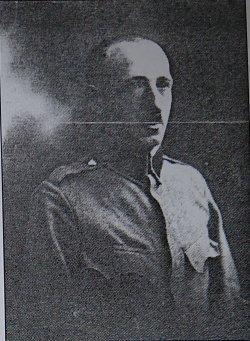

Ariah Suchman's father Zvi Yager-Suchman, z'l, in his youth in

Austrian Army uniform

Ariah Suchman's uncle, Yosef Leib Wasserman, z'l, in Austrian Army

uniform, later murdered by the Nazis.

Ariah Suchman's uncle, Yehuda Meshel-Wasserman, z'l

p. 37

Julius (Yehuda) Bretler in the Austrian Army during the First World War. He was

an accountant, merchant, storekeeper in Kolomyya, and cigarette manufacturer in

Berlin, Germany. Sons: Mos (Dr. Maksim) Bretler, born in Kolomyya in 1909,

Emanuel Yeshayahu Bretler born in Kolomyya, 4 December 1921, married Franya Esta

Blatt, Kolomyya, August 28, 1907.

Julius (Yehuda) Bretler in the Austrian Army during the First World War. He was

an accountant, merchant, storekeeper in Kolomyya, and cigarette manufacturer in

Berlin, Germany. Sons: Mos (Dr. Maksim) Bretler, born in Kolomyya in 1909,

Emanuel Yeshayahu Bretler born in Kolomyya, 4 December 1921, married Franya Esta

Blatt, Kolomyya, August 28, 1907.

The railway station in the village of Gody-Turka, near Kolomyya. The station was

built by the Kolomyya property owner, Yaakov Bretler, before the First World

War

The railway station in the village of Gody-Turka, near Kolomyya. The station was

built by the Kolomyya property owner, Yaakov Bretler, before the First World

War

Yaakov Bretler's brewery in a suburb of Kolomyya - Getkowitza

Yaakov Bretter's flour mill

p. 38

Mr. Yitzhak Teitlebaum

Yitzhak Teitelbaum, z'l, photographed at home in Haifa, March,

1992

In memory of Mr. Yitzhak Teitlebaum, our devoted friend, who gathered material for the memorial book of Kolomyya during the Holocaust. Yitzhak Teitlebaum made a wonderful contribution through his decades of active participation in the organization of The People of Kolomyya in Haifa. He was the first of the organization who started gathering documentary material in Israel and abroad, in order to bring this important and authentic material to publication in Hebrew and in Yiddish by the organization in a book memorializing the Jews of Kolomyya. The book was published in Israel and in the US, edited by Dr. Shlomo Bickell. Earlier Dr. Bickell had published a book, A Town and Its Jews in Yiddish in New York in 1942. The book was translated into Hebrew by Shimshon Meltzer. I hope that these books will remain as a memorial for this generation and generations to come, to read and to learn about the town of Kolomyya between the World Wars, until its complete destruction by the Nazis.

In September 1992, a memorial service was held in the Nahlat Yitzhak cemetery to mark 47 years since the destruction of the Jews of Kolomyya and its environs. That was the last year that Yitzhak Titlebaum participated in the ceremony. At the end of the service he asked for permission to speak. He addressed those present with his request to support the memorial project of filming a documentary about Kolomyya Jewry. Yitzhak Teitlebaum was a wonderful Jew, who worked intensively for the organization of Kolomyyans in Israel and abroad. For 20 years he labored at gathering the material for the Yizkor book of Kolomyya, which commemorated the destruction of the town of Kolomyya, which was and is no more.

At this ceremony, Rav Metzger spoke about the martyrs of Kolomyya who were murdered during the Holocaust. The film of the ceremony was a cornerstone for the historical project, which will present to coming generations the dimensions of the tragedy of the Holocaust.

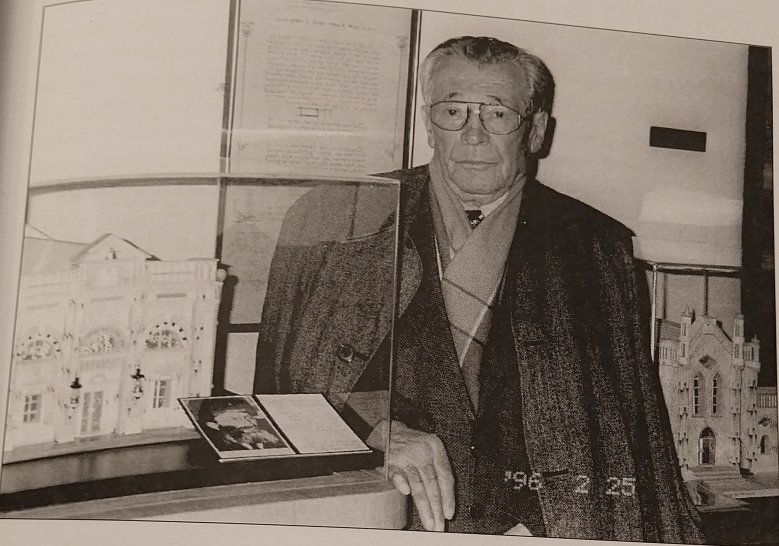

When Mr. Ya'akov Kinick, of blessed memory, participated for the last time in this ceremony, he gave his blessing and support to the making of the film, and his approval for constructing a wooden model of the Great Synagogue. Mr.Hanan Weissman, our friend and craftsman, constructed this model, which is now on display in the Museum of Witness at Nir Galim, where thousands of tourists and pupils visit every year.

p. 39

The town center in Kolomyya. Legionov Street, next to the Town Hall

building.

Sobieski Street, next to the Ukrainian Church. On the corner on the left, the

house of Yitzhak Teitlebaum z'l, who was for decades active in the

Organization of ex-Kolomyyans in Israel.

p. 40

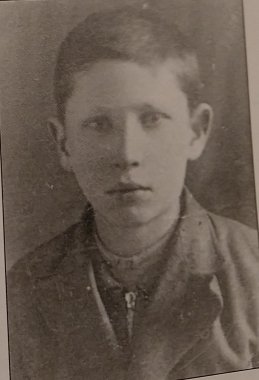

Edward Firestone, z'l - Holocaust survivor.

He was one of the leading activists in the ex-Kolomyya community in the

United States until his death.

p. 41

On the work of Edward Firestone z'l, survivor of the Holocaust from Kolomyya and activist in the Kolomyya community in the US

Edward Firestone excelled in his public activities for the general welfare. While still a young man in Kolomyya, he was active in Zionist youth movements and in establishing a sports club. He was appointed Chairman of the Sports Federation of the best football club in the second league.

There were three Jewish sports clubs in Kolomyya, and he headed Z.T.G Dror. The second club was Asmonia, and the third, Hapoel. From the early 1930's and onwards these clubs competed with Polish clubs in Kolomyya, and the matches often ended in fistfights, in which the Poles lost. Edward Firestone always tried to make peace between the sides and prevent the violence.

He owned a materials shop together with his younger brother until the war broke out in 1939, when the Soviets entered Kolomyya. Later when the Nazis seized the area in 1941, the family suffered as other Jews of Kolomyya. However, by a miracle, he and his family survived after going through the hell of the Kolomyya Ghetto. After the war they went to Poland, and from there to Frankfurt in West Germany.

In Frankfurt, the unexpected happened. Edward and a friend, a survivor from Kolomyya named Krauthamer, were walking down a street when to their amazement they stood face to face with a familiar figure wearing civilian clothes. They froze on the spot for the man was the head of the Gestapo in Kolomyya, the former SS officer Peter Leidrich, who had conducted the cruel roundups in Kolomyya and sent Jews to their deaths. Edward and his friend began to shout, "Nazi! Nazi!" A crowd immediately formed, and the American military police soon arrived. The frightened murderer was arrested and jailed in Frankfurt. In the initial investigation, Edward Firestone and his friend Krauthamer testified.Additional witnesses were also called, who also testified to the murderou activities of the butcher of Kolomyya. During his trial, his captivity became known to the Polish government, which requested his extradition. In a court in Warsaw, Leidrich denied his guilt, maintaining that he had only dealt with issues regarding the Galician border. After a lengthy investigation, on the basis of firm testimony, he was sentenced to death and hanged in a Warsaw prison in 1947.

Edward Firestone will be remembered for laboring day and night in the US, as chairman of the organization of Kolomyya Jews, to memorialize the Jews of Kolomyya. He was blessed with many years, and passed away with a sterling reputation.

May his widow, Julia and her son also be blessed for their continued activity in memorializing the Jews of Kolomyya, especially for their generous contribution to the production of the book Kolomyya Forever. My thanks, and the thanks of all Kolomyya survivors in Israel and the Diaspora go to Edward Firestone.

p. 42

Edward Feuerstein z'l, at a communal function of former Kolomyyans in the

United States, delivering a speech at the evening commemorating the publication

of the Kolomyya Yiddish community record book in 1957 in the presence of a large

gathering and the remaining survivors.

The Dror Z.T.G football team in the 1930s. At the start of a match

against a rival team on the 49th Battallion’s sports

field n Kolomyya. Edward Feuerstein, the chairman, is standing on the right,

next to the player Bolek.

p. 43

Yaakov Kuba Menashes

Attorney Yaakov Menashes visiting the exhibition of model synagogues in the House of Witness at Nir Galim. Yaakov Menashes was born in Kolomyya in 1906. He was one of the leaders of the Revisionist Movement in Poland and a well-known Zionist orator who was privileged to work closely with Zeev Jabotinsky. He held the post of secretary of the movement for eastern Galicia, whose towns and townships he frequently visited and attracted large crowds.

p. 44

p. 45

p. 46

p. 47

p. 48

p. 49

p. 50

p. 51

p. 52

p. 53

Rabbi David from Kolomyya reveals the greatness of the Baal Shem Tov

TODO: type up the text of this section (pages 44 through 47), and add the images and corresponding captions (pages 48 through 53)

p. 54

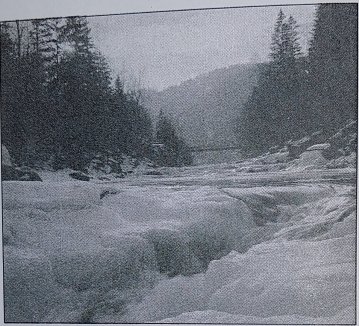

Beautiful pastoral scene of the Carpathian mountains in the area of eastern Galicia where the Baal Shem Tov, the founding father of Hassidism, would go into seclusion until experiencing a revelation.

The River Prut frozen over in winter.

The River Prut in the summer.

The snowy Carpathian

Mountains in the winter near the Polish Hungarian border before the

outbreak of the Second World War. Smugglers crossing the Polish-Hungarian

border during the Holocaust used the mountain on the left.

p. 55

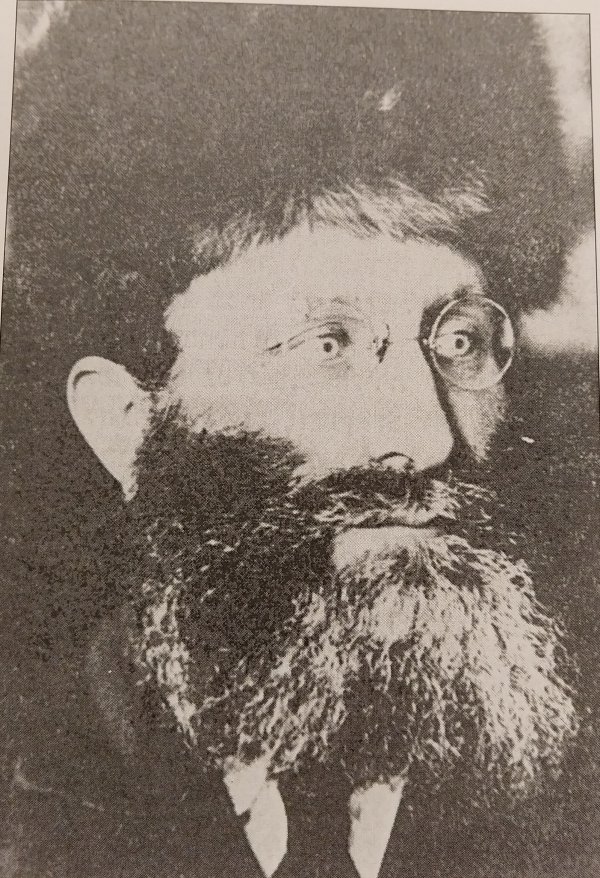

The last Rabbi of the Kolomyya community, the Great Rabbi Yisrael Yosef Lau, z'l, who died in the Holocaust

p. 56

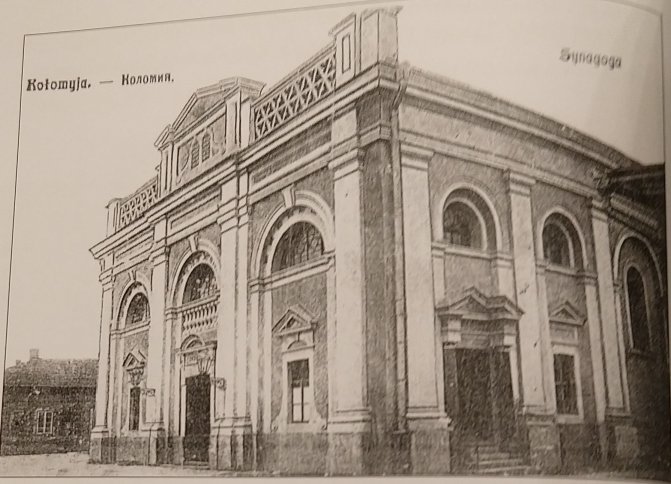

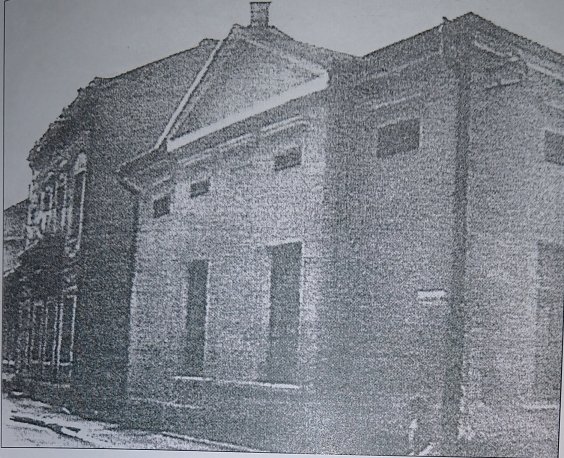

The Great Central Synagogue of Kolomyya where the last rabbi of Kolomyya,

Rabbi Yisrael Yosef Lau, z'l, prayed. The synagogue was torched by the Nazis on

the night of Hashanah Rabah, 1942.

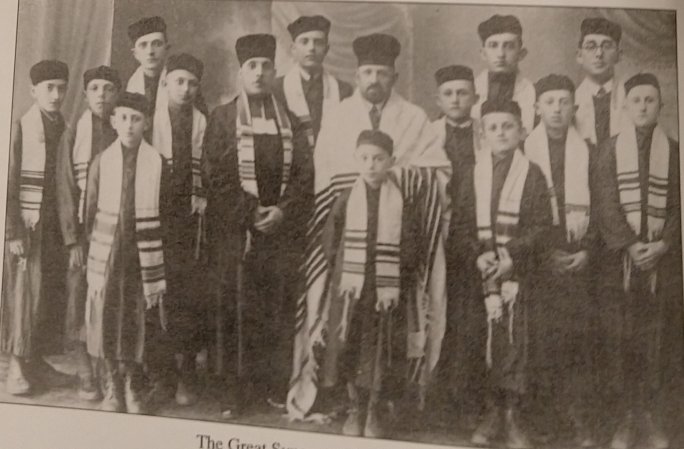

The Great Synagogue's choir, 1930s.

p. 57

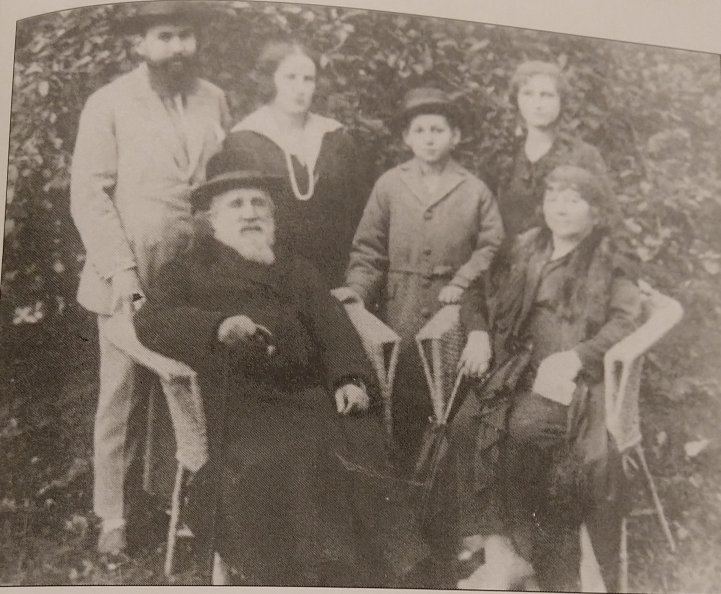

Rabbi Hirsch Leib Lau and his wife sitting in the garden of their house in

the city of Lvov. The parents of the two brothers, Rabbi Yisrael Yosef Lau,

z'l, the Rabbi of Kolomyya and Rabbi Moshe Lau, z'l, Rabbi of

Pyotrikow. The young boy in the center, Shmuel Itche, was the son of Rabbi

Yisrael Yosef Lau, z'l.

(The picture was reproduced

with the kind permission of the Chief Rabbi Yisrael Meir Lau, Shelita, son of

Rabbi Moshe Lau, z'l.)

p. 58

The Rabbi of Kolomyya, Rabbi Yisrael Yosef Lau, z'l, swearing in

Jewish soldiers into the Polish army. The ceremony took place in the 1930s in

Kolomyya on the sports field of Battalion 49 in the presence of town dignitaries

and Army officers.

A game between two Jewish teams, Dror Z.T.G. and Simona on the sports

field of Battalion 49 in the 1930s.

p. 59

Rabbi Israel Yosef Lau uprooted the tombstone

From the book Remembering Kolomyya by A.S. Rina

The Rabbi's voice trembled. His face was ashen. Tears streamed from his eyes. He spoke haltingly: "Oh Holy Graves, Holy Dead, Holy Bones. Please forgive us for this wicket iniquity, for desecrating your honor. It has been decreed that we shall desecrate the holiness of your graves. We have to uphold this decree in order that your children and your children's children shall live. We beseech you, the Holy Dead, to forgive us. May our prayers and supplications multiply before the Almighty God. We pray mercy for Israel and the nation of Israel that has suffered so much affliction. Forgive us, Oh please. Forgive us"...

The thousands of Jews that stood with bowed heads and stooped backs among the many graves that covered the cemetery heard every word that was uttered by the Rabbi. They followed his words with sighs and silent lamentations. They watched the local Rabbi raise his pale white hands upwards, his voice choking: "Our Witness in Heaven, we are compelled" The Rabbi sobbed bitterly and with him the whole assembly began to wail.

With trembling hands the Rabbi touches the tombstone that is before him. He drenches the stone with his tears. He momentarily steps back and grabs his hands as though he had touched a burning rod. Once again he sends his quivering hands to the tombstone. The Rabbi's eyes are closed. His face contorted. He hugs the tombstone like a compassionate father would hug his only son. He breaks into a wail and begins to wrench the tombstone from its place ... The head of the community and its respected members soon join the Rabbi. They also begin tearing the tombstones from their places with piercing cries. The rest of the community that had come to the cemetery also began tearing the tombstones from their places.

That was between Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur in 1942. The nazi commander of Kolomyya (in eastern Galicia) had plotted this heinous deed. The Jews of the city had been commanded to uproot the tombstones from the graves in the cemetery in order to pave roads for the German army's armaments to pass over. The day after Rosh Hashana in 1942, a Nazi captain came to the Gestapo that had the head of the Jewish affairs in Kolomyya under its jurisdiction. They demanded that the following morning several hundred Jews be sent to uproot the tombstones from the graves and transport them to the roads. An elderly Jew ran to inform the Rabbi of the city, Rabbi Israel Yosef Lau.

On the same day a meeting was called at the Rabbi's house with all the respected members of the congregation. Many said that they should not comply with the Gestapo demand and that they would prefer martyrdom sanctifying the name the Lord, rather than execute this terrible injunction of desecrating the honor of the dead of the city. The Rabbi was of a different opinion. In a broken voice he explained that it is not proper to desecrate the dead, but he conceded, that according to the Torah this would not be considered a capital offense. He stressed that "If this heinous deed is to be done at all, it will not be done p. 60 by 'simple Jews'. I will be at the head of this and together we shall go to the cemetery and take upon ourselves this sinful task. "The congregation accepted the Rabbi's decision and dispersed in silence. The following day the whole city was plunged into a public fast. The Rabbi was immersed in prayers and recited the Slihot and thereafter the respected Elders of the city went to the cemetery. When the word got out that the Rabbi had gone to the cemetery, there was a flood of Jews from every corner of the city. The Rabbi looked into the faces of his community that stood before him with bent heads and wrapped in silence. They stood for a few minutes in reverence. They watched the Rabbi, his lips moving in prayer. And then the mournful declarations burst forth from his mouth - to the Holy tombstones...

That deed saved the lives of many Jews in Kolomyya for another year. At the end of that year, the remaining Jews of Kolomyya with the Rabbi Israel Yosef Lau at their head, were sent to the concentration camp Belsac.

p. 61

Jewish gravestones

uprooted by order of the Nazis by Jewish slave-labor among whom was Rabbi Yosef

Israel Lau z'l. The Nazis used the stones to pave paths to the houses of

SS officers. After the liberation of Kolomyya and under Soviet rule, the

gravestones were collected and placed in the square where previously the statue

of Lenin had stood.

The statue of Lenin in the central square in Kolomyya placed there by the

Soviets in 1939-40.

p. 62

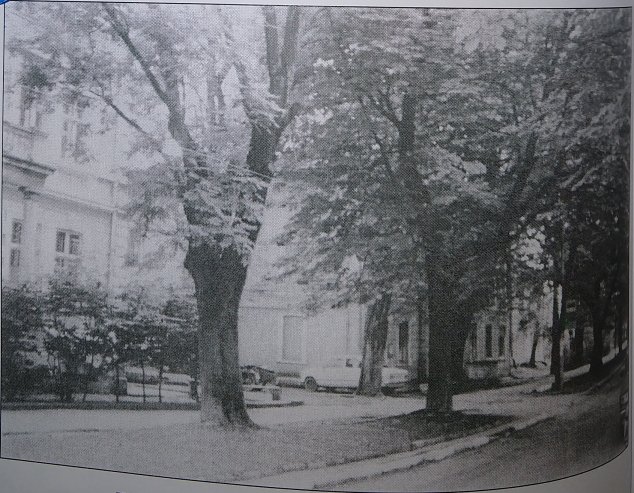

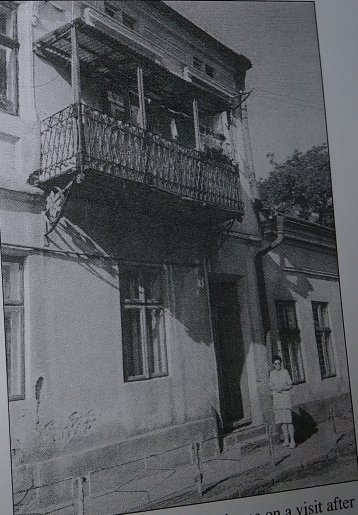

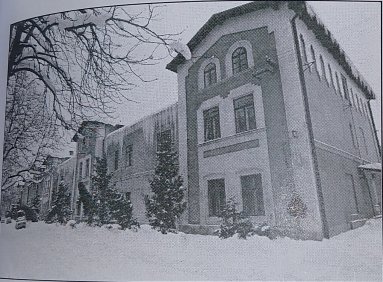

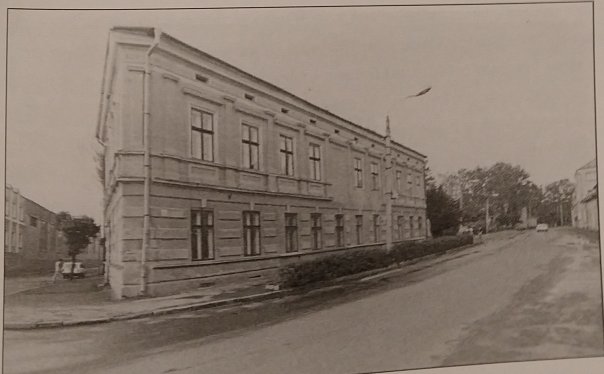

Rabbi Lau's house in Kolomyya. The house remained in tact during the Holocaust

and has remained unchanged until today.

Welnoshtzi Street, near the house of Rabbi Israel Yosef Lau, z'l,

p. 63

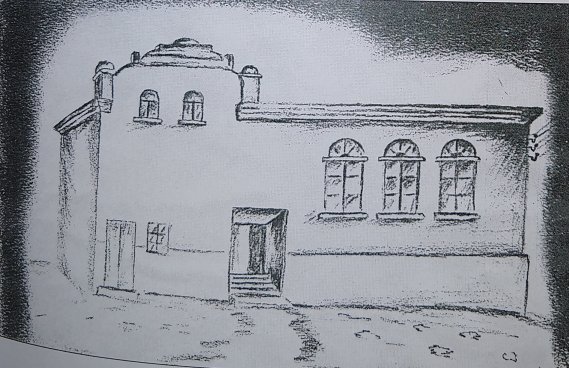

The DeYerushalayim Synagogue that survived the Holocaust is found near

the Central Square of Kolomyya. On Sabbaths and Festivals, services are held by

the few remaining Jews in the area.

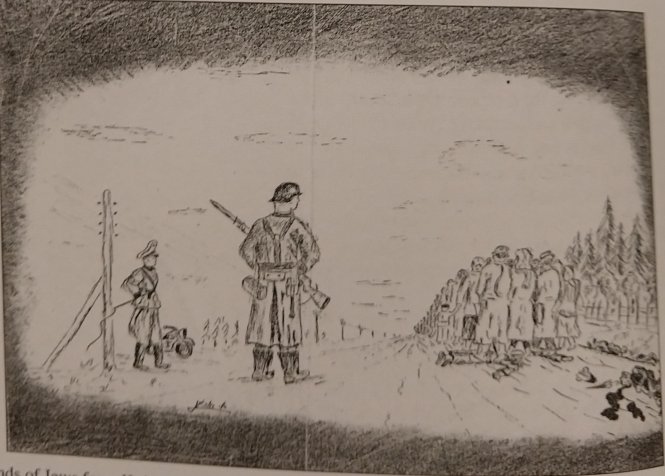

A drawing by Ariah Suchman.

The Synagogue Bojan Klaus Hassidim in

Kolomyya. Ariah Suchman's grandfather, Yaakov Suchman, z'l, was the last

sexton of the synagogue. On a Shabbat in 1942, the Nazis broke into the

synagogue during the service and started murdering the congregants. Tens of

congregants were murdered in the synagogue among them was Yaakov Suchman, z'l.

After the orgy of murder, the Nazis burned down the synagogue and nothing of

the building remains today.

p. 64

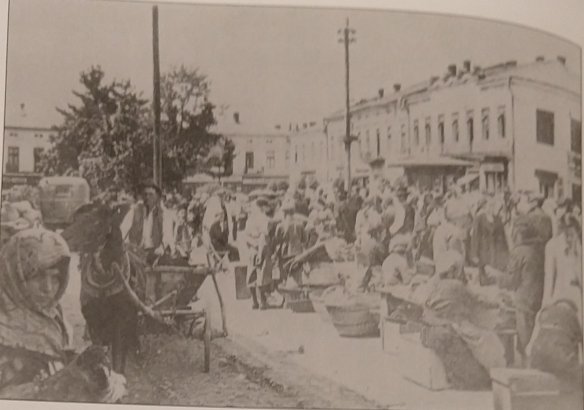

The famous marketplace (Der Markplatz) in Kolomyya. The photograph

was taken before the war.

The Polish National Gymnasium in Kolomyya where both Jews and Poles

studied.

p. 65

The Rabbi with his pupils in the Talmud Torah

A sketch of the Talmud Torah as it appeared before the outbreak of the

Second World War by Ariah Suchman.

p. 66

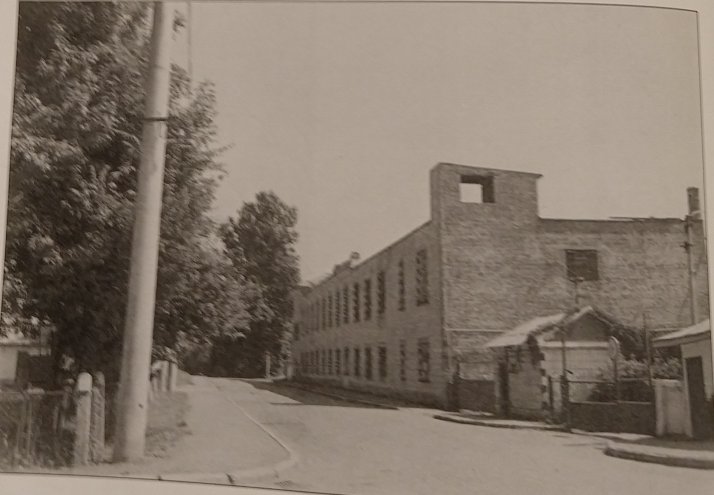

The Zaiger Prayer Shawl (Tallitot) Factory

The Shimshon Heller's Prayer Shawl Factory. Today the two factories

produce fabrics.

p. 67

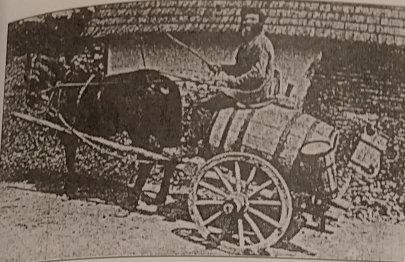

Jewish water-carrier.

A sketch of a Jewish water-carrier on his horse and cart by Ariah

Suchman.

A sketch of the great well in Kolomyya by Ariah Suchman. This well is

mentioned in the book In Praise of the Baal Shem Tov.

p. 68

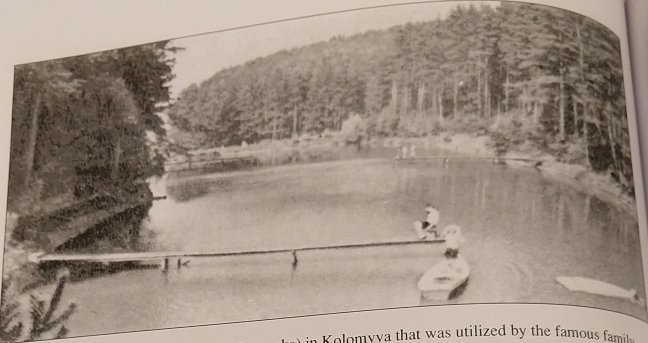

A tributary of the River Prut (The Mlynowka) in Kolomyya that was

utilized by the famous family Bretler flourmill.

A wooden bridge across the River Prut.

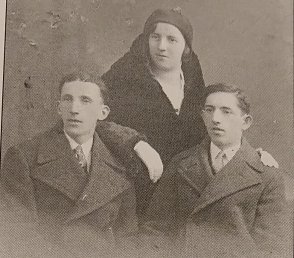

A group

HeHalutz HaZair members canoeing. The boy in the left corner of

the picture is the author's eldest brother, Moshe, and the boy third from the

right was his brother-in-law, Menachem Zvingeler, z'l.

The picture

was taken in the 1930s.

p. 69

The Prut River in Kolomyya, August 1994

The bridge over the River Prut photographed in 1997 during a visit by

former Kolomyyans to the area. According to tradition, the Baal Shem Tov used to

cross this bridge in order to reach Kolomyya to earn his living and also to pray

in the Hassidic Kossov Synagogue in the Jewish quarter.

p. 70

Documenting the Holocaust of the Jews from Kolomyya and its Environs on film

The project commemorating the Jews of Kolomyya began between the years 1991-1993, in the framework of my activities in the organization of former Kolomyyans. I suggested to the late Mr Yaacob Kinik, the chairman, that there should be a commemorative project, to which he gave his blessing and encouragement. I began to work on the project unhesitatingly, not taking into account the financial and technical difficulties that would be involved in the preparation of a project of this magnitude. It was a God-given sacred mission.

At the 47th memorial service that was held at the cemetery in Nahlat Yitzhak, Rabbi Yona Metzger and many former Kolomyyans attended including the late Mr Yitzhak Teitelbaum, the chairman of the organization of former Kolomyyans in the Haifa area. Mr Teitelbaum was at that time collecting material for a memorial book of the Jews of Kolomyya. He publicly endorsed my project and turned to the people participating in the ceremony asking them to assist towards this sacred project. And so we set out on our project seven years ago; seven years of uninterrupted work often running into days and nights.

During the 47th memorial service for the murdered Jews of Kolomyya in September 1991, I filmed the ceremony. When I watched the film later with my friends, I felt very touched that the event had been documented, and decided that despite the many difficulties that stood in my way, I had to begin the project, at any price. I would give up days and nights for this project, and also as much money as I could to see it finished.

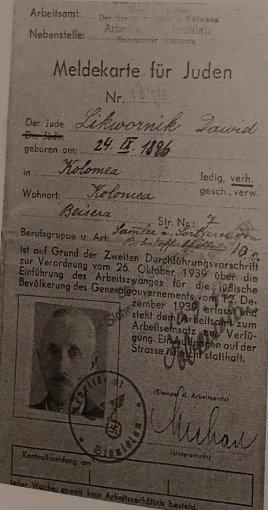

When the ceremony was over, and having completed filming the first video, Yeshayahu Likvornik, a fine Jewish man who survived the atrocities of the ghetto in Kolomyya when he was 12 years old, approached me and asked if I was making a film on Kolomyya. I told him that indeed I was making such a film because I felt that it was very important to perpetuate the memory of the Jews of Kolomyya and its environs. Yeshayahu looked at me with a touch of emotion and a smile on his face as he thought about his mother, brother and sister who were sent to the death camp in Belzec. Only he and his father had miraculously survived. He invited me to his house so that I could hear his difficult story, and perhaps include it in the film.

I arrived at Yeshayahu Likvornik's house equipped with a tape recorder. I was warmly received and we began our interview with his personal story from the time that the Nazis first entered Kolomyya right up to when the city was liberated by the Russian army on 28th March 1944. It was very touching to listen to the stories of the memories of his youth and his family and I was filled with wonder by the fact that he remembered every detail from that period and the exact dates of all the terrible acts that the Nazis had committed and the dates of the transport of the Jews on the death trains to Belzec.

p. 71

Within two years I had succeeded in documenting all the stories of horror from the Kolomyya ghetto. This material served as the basis for the preparation of the filming of the first interview with the Holocaust survivor from the Kolomyya ghetto - Yeshayahu Likvornik. I should emphasize that he is the central person in the film Kolomyya during the Holocaust owing to his unusual stories.

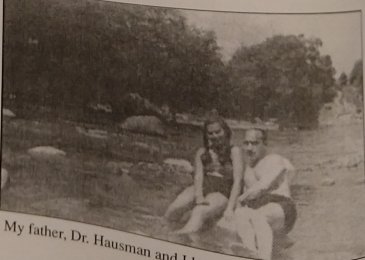

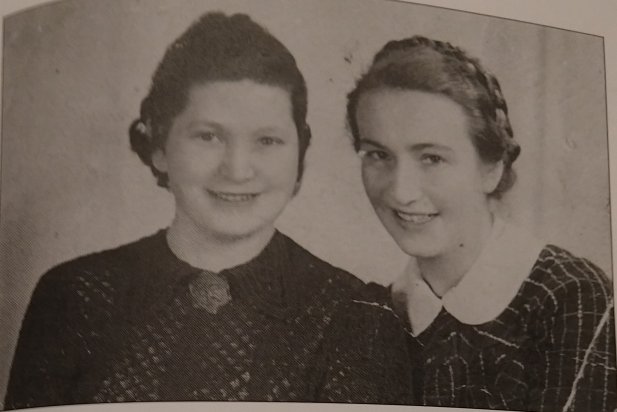

This interview led me to other survivors from the Kolomyya ghetto, eight of them, who related their stories from that period - amongst them Professor Maria Rosenbloom Hirsch, who now lives in new York, and the late Professor Blanca Rosenberg, the wife of Dr Rosenberg from Kolomyya who was the director of the hospital during the period of the Russian occupation and was inducted into the Russian army when it withdrew from Kolomyya on 29th June 1941.

I do not know why Yeshayahu Likvornik approached me to listen to his story about the ghetto of Kolomyya, maybe he had the feeling that I was the right man upon whom to place the responsibility of documenting the destruction of Kolomyya by the Nazis.

I have to tell you my friends, former Kolomyyans living in Israel and the Diaspora, that without Yeshayahu Likvornik, we would not have had the opportunity of perpetuating the memory of the Jews of Kolomyya who were annihilated by the cursed Nazis. He brought us important and authentic material of the horrible riots that took place in the city and exact dates of the aktions and transportations of the victims to the death camps. He suffered through these horrific riots until the ghetto was destroyed and he escaped with his father, the late David Likvornik, with the help of Vasilian Petrovski, a Ukrainian and Righteous Gentile who endangered his and his family's lives in order to save 18 Jews from the hands of the Nazis.

Likvornik and his father remained in hiding for 14 months under terrible conditions fearing they would be discovered until they were liberated by the Russian army, which entered the city on 18th March, 1944. Yeshayahu told me that he would never forget that day because that was the day he emerged from darkness to the light and the air of the world. God mercifully gave them life and they were reborn. It was a sad day too because only he and his father had survived and they never saw their mother, sister Tami and brother, Meir, alive again as they had been sent to die in Belzec. May their dear souls rest in peace.

We, the sons of Kolomyya in Israel and the Diaspora, owe our thanks and recognition of the contribution that Yesheyahu Likvornik made. He encouraged us to commemorate our dear ones who died sanctifying the Holy Name. It is owing to him and his initiative that the film came about in two parts: the ceremony honoring the Righteous Gentiles Vasilian Petrovski and his sister Anya, which took place at Yad Vashem in Jerusalem on 12th November 1997, with the participation of the survivors of Kolomyya, and Professor Dov Noy and a group of high school students.

Behira Zakai, one of the survivors, made a speech that described her suffering in hiding as an orphan with her younger sister after her mother had died in hiding six months before the liberation. It is owing to Behira Zakai that a new chapter has been written in Yad Vashem in memory of the late Vasilien Petrovski and his sister Anyah. The ceremony was presided over by Dr Mordechai Paldiel and the p. 72 deputy chairman of Yad Vashem, Mr Yochana Bein.

The second and main film is the full documentation of the destruction of the Jews of Kolomyya during the Holocaust, where eight survivors relate in detail about the day that the Nazis entered Kolomyya. I hope that our efforts in the preparation of the film with the testimony of the survivors will prove to be valuable for the coming generations and will substantiate for them the tragedy and the destruction of approximately 80,000 Jews of Kolomyya and its environs.

The survivors narratives in the film do not appear in the memorial book of the Kolomyya population. These are new and difficult stories about their escape from the ghetto with the aid of the Righteous Gentiles of Kolomyya.

I would like to state that Mr Tuvia Friedman, Head of the Institute for Documentation and Research into Nazi crimes was interviewed in the film and he tells of the crimes perpetrated by the Nazis in Kolomyya and about the fifteen Nazis who were brought to trial. They were apprehended in Vienna in 1947 with the help of the Russian authorities and were extradited to Siberia.

We faced many problems in the production of the film. Most of the film is made up of still photographs and video, which were filmed in Kolomyya over three years and then brought to Israel. Work began while the communists were still in power, and there was the danger that the film might be confiscated. It was our good luck that we had good relations with non-Jews in Kolomyya who helped us get this important material out. We had to pay them, but it was important to have this authentic material.

Similarly we had problems financing this work, especially in completing the project; the heaviest costs being the editing of the film in the editing studios by a professional editor. A 10-hour day editing job costs $600. This work can continue for a month and a half and includes expenses of recording the interviews with sound, translation, the narration into English, which all come to tends of thousands of dollars. The project will cost over $35.000, money that we obviously did not have. We first approached the Ministry of Education, the late Mr Zevulun Hammer, the then Minister of Education, as we knew he was particularly sensitive to the Holocaust issue. He passed on our request to his advisor who passed it on to the head of the film department at the Ministry of Education, Mr Boris Mafzir. Mr Mafzir met with us and promised to finance 30% of the cost of the project, but to our disappointment we received nothing.

I think that this sacred mission was a bidding from heaven. It makes a contribution toward substantiating the events of the Holocaust for future generations. It helps to explain the magnitude of the crimes and cruelty perpetrated by the Nazi criminals who exterminated the Jews of Kolomyya in eastern Galicia and the annihilation of the Jews of Europe in general during the Second World War.

A film commemorating the destruction of the Jews of Kolomyya is important for those doing research on the Holocaust and could thus serve educational institutions both in Israel and abroad.

I thank the Lord for making it possible.

Ariah Suchman

p. 73

The film: The Jews of Kolomyya

The documentary film on the destruction of the Jews of Kolomyya and its surroundings in Eastern Galicia (the old Poland) deals with Kolomyya from its early beginnings until its destruction in the days of the Holocaust during World War II.

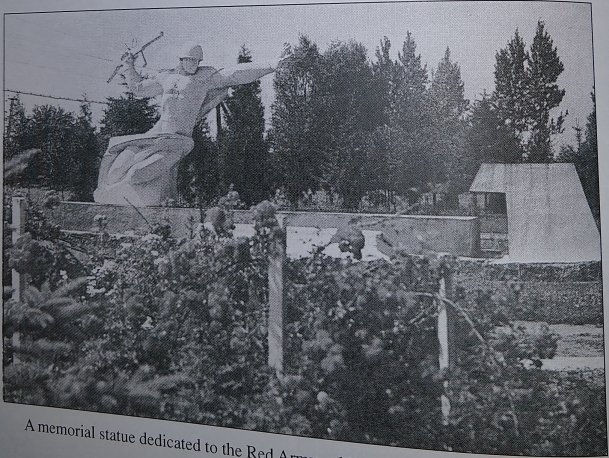

The film presents the events that took place in the Kolomyya ghetto during the Holocaust from the day the Nazis entered the city until its liberation on 29 March 1944, by the Soviet army. The hero who commanded the liberating forces was General Botschkovski, a national hero who is assumed to have been Jewish.

A monument was erected in memory of the fallen soldiers, amongst whom were a number of Jews. May they be remembered for ever.

The entrance of the Soviet soldiers into Kolomyya bestowed a new life on the few remaining Jews who had been hidden by the righteous Gentiles in Kolomyya.

The Second World War and the Holocaust brought an end to the Jewish settlement in Kolomyya and its environs - a settlement that had begun in the 17th century.

Our commitment

We, the last generation of the children of Kolomyya and its environs pass on to our descendants the memory of the horrors of the past that filled our lives. May the commemorative film, The Jews of Kolomyya during the Holocaust, and this book serve as historical documents for future generations, as a memorial for the sacred souls who went up to Heaven in a terrible storm in those dark days that fell on Kolomyya and its environs during the Holocaust.

In the name of the survivors of the Holocaust from the Kolomyya ghetto, we express our deepest thanks to all those who supported us both in Israel and the Diaspora, those who aided us in the completion of the film and this book commemorating the Jews of Kolomyya and its environs who perished in the Holocaust.

Your names will be remembered and we shall be forever indebted to you for your contributions to the commemoration of this sacred purpose.

Ariah Suchman,

Producer

p. 74

The Documentary Film "The Jews of Kolomyya during the Holocaust"

by Arieh Suchman, Producer and Director

TODO: page 74 has not yet been typed/etc.

p. 75

A brief history of modern Poland and Galicia up to the German occupation

In the 18th century, Queen Maria Theresa married the German Duke Franz Stephan Lorient Lutrigen and established the new branch of the Lutrigen Hapsburg dynasty. Maria Theresa was a tall, blonde, stately woman. She was calm and serene, and she was as kind as she was down-to-earth. She was a good mother to her sixteen children. She was plain, but blessed with outstanding emotional strength and an exceptional talent for politics.

Maria Theresa, a patron of the arts, amended many aspects of the government. She nullified the cruel methods used in investigating defendants and established public elementary schools. During her reign, municipal sanitation services were established, a necessity considering the sanitary conditions of the time.

Despite all of Maria Theresa's qualities, she was nonetheless an anti-Semite, and caused the Jewish people great suffering. Maria Theresa ordered the expulsion of Jews from many places, particularly from Prague, the capital of Bohemia, but she was unsuccessful in implementing all of her restrictions. It was during her reign as queen, in 1772, that Galicia was annexed to Austria, following the first division of Poland. This annexation immediately doubled the Jewish population in the Austrian kingdom.

The queen's son, Joseph the Second, introduced reforms that eased the plight of the Jews under the Austro-Hungarian regime.

During WWI, the Austrian army conducted fierce battles on all the western fronts against the Italian army, which was striving to regain control of Tyrol that had been conquered by the Austrians. The Italian army, having earlier on won several battles, succeeded in overcoming the Austrian army.

In southeast Galicia, in Bukovina, Yugoslavia, the Czech Republic and Hungary, the Austrian army suffered defeat by the Russian army. The Austrians fought braavely in the Carpathian Mountains, and despite the loss of thousands of soldiers, the Russian army was unable to defeat the Austrians, or to bring about Emperor Franz Josef's surrender. During the fighting, the Bolshevik revolution broke out, turning things around on the battlefield for the Austrians.

During this time, the Austrian army also suffered losses in northern and central Poland. The Polish Legion, under the leadership of Marshal Pilsudski and Gemeral Haller, tried to limit the presence of the Austrian army in Poland, and to liberate Poland from the foreign occupation between the years 1919 - 1921. The result was the new Polish Republic, with Germany on its western border, Prussia on the north, and the Bolshevik regime along the long eastern border. Rumania, the Czech Republic and Hungary bordered on Poland in the south, along the Carpathian Mountain range.

WWI ended in the Austrian defeat, resulting in an Austria diminished in size. Poland became a large and powerful country under the leadership of Marshal Pilsudski (1921-193) who was a popular leader, and p. 76 the anti-Semitic Poles often noted that he was the protector of the Jews.

Jewish refugees began returning to their homes in eastern Galicia during the late 1920s and early 1930s, only to face the destruction and ravages of the war. Slowly, life began to return to normal. The Polish regime allowed the Jews to deal in commerce and industry, to serve in the army, to study in the high schools and universities. These rights were not easily achieved, and a long and arduous struggle was fought before the Jews were granted the same rights as other Polish citizens.

One of the reasons the third Reich was able to rise to power in Germany was the economic crisis and the severe unemployment. These conditions led to the election of an extremist, Nazi government, headed by a new demon — the nefarious Adolf Hitler. He trapped the German people, who awarded him their full trust. The elderly Chancellor Hindenberg, defeated and humiliated, resigned from the Parliament, leaving the way for Hitler to resolve the national crises, to build up a powerful military industry and prepare the country for war - a war no one could have predicted the results of. The evil speeches delivered by the Nazi oppressor were soon heard throughout Europe, particularly in Poland. The Jews began to sense a black cloud of doom approaching from the western border. They heard the resulting voice of the Nazi army over the radio as they marched through the streets of Berlin shouting "Heil Hitler, as the smiling fuhrer waved at the German crowds anticipating their imminent conquest of the entire European continent.

Evil, venomous voices of incitement and agitation against the Jews could be heard daily over Radio Berlin. The Jews of Poland lived in fear of the Nazi oppressor and the impending invation of Poland. The beloved leader, Marshal Josef Pilsudski, knew what was going on in Nazi Germany. He also understood that the Polish army, armed with outdated weapons and not trained in modern warfare, did not stand a chance against the great German army with its thousands of tanks and airplanes. Marshal Pilsudski was aware of the inevitable future his people and country faced should the Nazi army invade Poland, but he was impotent against the desire of mighty Hitler to conquer all of Poland. In the mid-1930s, Marshal Pilsudski died. All of Poland grieved the loss of their admired leader; millions of Poles flooded the streets to participate in memorial services. The Jews also conducted memorial services, attended by the chief rabbis, mayors and Polish military figures. Slogans, directed toward the Jews, appeared in the streets of Poland, "Your father and grandfater are dead. These were the first signs of Polish anti-Semitism of that time.

Within a short while, Polish Jewry was living in fear. Poisonous anti-Semitism was rampant on the streets of Poland. The Endecja (Polish Nazi Party) recruited its members from the high schools and the universities. The situation worsened, and outbursts of anti-Semitism became increasingly common, with Jews being attacked, often brutally. The German army's invasion of Poland was expected any day. The Polish people paid a heavy price when the Nazis invaded their homeland, but Polish anti-Semitism was deep rooted and needed little prodding from the Germans. They were eager to see Poland free of Jews, and to claim all Jewish property for their own.

In 1939, the Polish people were preparing to protect their homeland from invasion by the Nazi army. p. 77 The Polish army and people prepared themselves, and the civil guard in the cities made preparations for chemical warfare. Radio Berlin continually denigrated and vilified both the Poles and the Jews. The Nazi army paraded in the streets of Berlin, flaunting their tanks in front of sympathetic crowds of millions. Hitler's voice could be heard over the radio, frightening the Polish people, as well as citizens of the other countries he intended to invade.

Kolomyya was located far from the German border and from the dangers of bombings and destruction. The Polish population was not prepared for the possibility of the total devastation the Nazis engineered throughout their homeland, the most brutal and barbarian annihilation ever known to mankind. Kolomyya was relatively calm when the war began. Everyone listened attentively to the radio, and there were many sleepless nights as everyone waited to hear news of the nation's fate, now so unsure and in the hands of God.

As the invasion of western Poland grew closer (September 1, 1939), the population began to hoard basic supplies. They spent all their savings to ensure there would be sufficient food in their homes at the hour of need. Merchants grew rich, amassing great quantities of Polish money, which later became valueless.

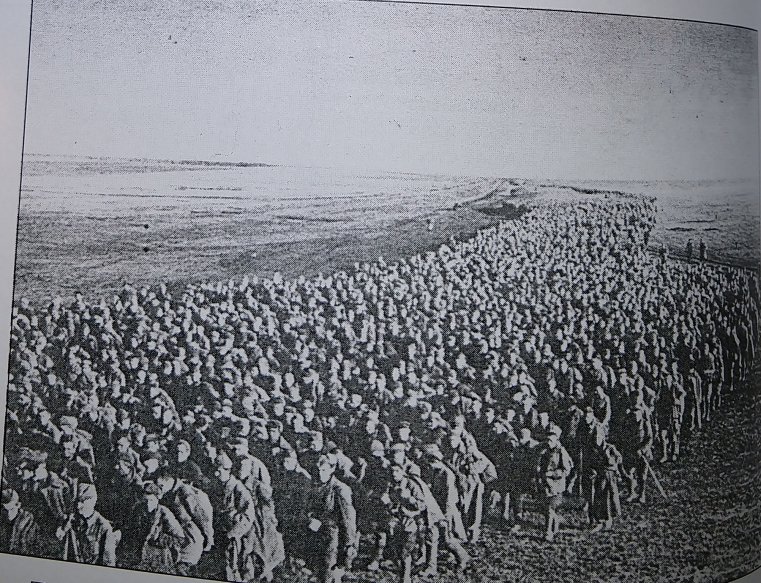

The Nazi army invaded with great force along the western Polish border, with every city in western Poland suffering from heavy bombings. Warsaw was hit the worst. The city protected itself bravely, and thousands of soldiers fought like lions, holding back the occupying forces for two weeks. The bombing went on for days. The Polish army did all it could to protect the city against the Nazi army that attacked again and again with heavy artillery. But the Polish army was unable to halt the invasion, and after three weeks of battle, the army surrendered. In the end, Warsaw surrendered after paying a heavy price while severe fires left the city badly scarred. Thousands of soldiers and officers were captured by the Nazi army and led in groups to detention camps. Also thousands of Polish soldiers, Jewish officers among them, were taken captive following the Russian invasion of east Poland in 1939. Later, many of these soldiers and officers were murdered in the Katyn forest, others were sent to forced labor camps in Russia.

During the first days of the war, sirens were heard in Kolomyya, warning the population against the enemy air attacks, but the city was saved thanks to the Molotov-Ribbentrop Agreement, which divided Poland, the west falling under German rule, and the east falling under Communist rule. Thus, during the height of the Nazi invasion, which had almost reached Lvov, Kolomyya woke up one to the sight of Russia tanks quickly entering the city center and flying the red flag from atop City Hall. The population of Kolomyya was relieved. Everyone spilled out into the streets to greet the redeeming Russian army with flowers and candy. Kolomyya was saved from complete destruction, and along with other parts of eastern Galicia, it fell under Russian rule. The Jewish population was saved from the horrifying fate that the cities of west Poland suffered.

In September 1939 the Russian army entered Kolomyya, and the Jewish and Polish population became accustomed to the new regime. The Russians made sure that all residents were employed, both Jews and non-Jews. The Jews managed well with the Russian regime, even better than before. They worked p. 78 where they were placed, and made a living. The population learned to live with the new regime, while hoping for a brighter future.

The Ukrainian population, fiercely patriotic nationalists, did not come to terms with the new regime. They were anxious to see Nazis in power so that they could settle their account with the Jews, wipe them out and appropriate their property. This had been their plan from the days of Chmielnitski.

In a period of twenty-one months, from September 1939 until June 1942, the Germans acted in west Poland to isolate the Jews in ghettos in preparation for their destruction. Many Jews were shot during this time. In a few instances, the Germans deported Jews to the east, to the area of the Soviet occupation. A small number of Jews managed to escape to Soviet territory. However, the majority of Jewry in west Poland remained to meet their bitter fate.

At this time the Soviets ruled east Poland, and in accordance with communist tradition, they arrested the wealthy and the property owners and deported them to Siberia and to other areas in the Soviet Union. This was the fate of the affluent Jews of Kolomyya, and while the deportation was against their will, it was what saved them from the destruction that was the fate of the less fortunate Jews of Kolomyya and the surrounding area after the Germans occupied east Poland.

p. 79

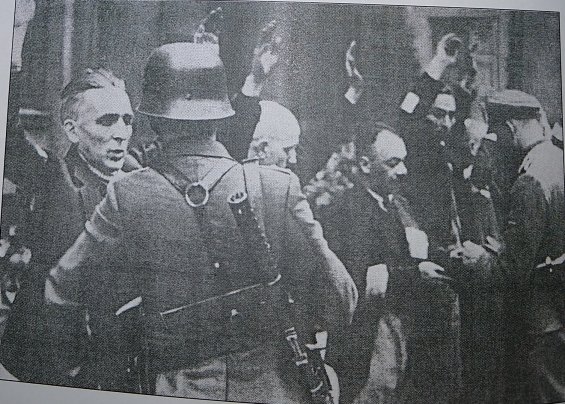

The Out-Break of War between Russia and Nazi Germany (June 22, 1941)

& the Dramatic Developments in and around Kolomyya

The Jewish population began to fear for their lives. Tears welled up in the eyes of all, especially the women, in anticipation of the inevitable. All deliberated regarding the most difficult and fateful decisions - should they stay, or pack up and flee with their families? Should they attempt the flight by train, cart or even by foot to escape the bitter fate of lynch or revenge by their gentile neighbors, particularly the Ukrainians and Poles who eagerly awaited the Nazi invasion to "settle accounts" with the 'Yids'.

Those that decided to leave immediately went to the train station, with only a small valise holding no more than a spare pair of trousers, or an extra coat, or a loaf of bread for the way. From their worried faces, it was clear that they were far from certain that they would actually board the freight train about to leave the station heading for the Russian border. Their only wish was to escape the city immediately, for fear of what they could expect.

Hundreds crowded the train platform in an attempt to flee the city, only to be disappointed. Two freight trains stood at the station, bursting with members of the Soviet army with their families and the possessions they had accumulated during the Communist regime in Kolomyya. The station was surrounded by soldiers and policement who allowed only certain people to board the trains and leave the city. Even those Jews connected to the Communist regime were helpless. Thus, two trains waited on the platform in Kolomyya, packed with Russian soldiers and their families, ready to leave for the Russian border at any moment, while the Jews of Kolomyya were unable to save themselves by boarding the trains. At critical moments like these, people find themselves considering their best moves and weighing up where fate will treat them less cruelly.

On the second day of the war, at 11:00 AM, amid the noise of the crowded train station, the hum of planes could be heard. The crowds at the train station looked up as the planes descended to drop their bombs on them. The sound of anti-aircraft gun's firing pierced the air, and luckily for those at the train station, the guns shot down the planes before they could drop their deadly bombs on the station.

The people in the station, understanding that their city also was in danger of being bombed from the air, tried to force their way on to the over-crowded train. Members of the army and police, already on board the train stopped them, thus determining the fate of the Jews of Kolomyya. Many tried to escape by foot, bicycle or carts, making their way through Ukrainian villages in the direction of the Russian border. Most of those who fled were young men, members of youth movements or students who escaped through fields and avoided all known roads.

The devil awaited them on the sides of the roads leading to the border. Few reached their destiny, and those that did get to the border arrived hungry and exhausted. The German planes bombed the roads leading to the border, as well as the bridges and train tracks, making progress very nearly impossible.

Hard times hit the city. Parents accompanied their conscripted sons as they left for the front. Mothers hugged their sons, weeping with the thought that they may never see their beloved sons again. Grandparents walked with grandchildren, mumbling prayers begging that their young be delivered from p. 80 the fate they knew in their hearts awaited them. They prayed that for the young who had never had a chance to enjoy life, be spared from all harm. Despite the anxious prayers, few returned from the war. The Russian army's retreat from Kolomyya and its environs tragically ended in failure. The Nazi army swiftly advanced in eastern Galicia, and the Nazi tanks overtook the large Russian forces, now downtrodden and retreating. Thousands of soldiers, many of them Jews, were unable to cross the border. They were taken prisoner by the German forces, and shipped to camps. There they were systematically murdered to the last man.

Hundreds of Nazi planes continuously bombed the cities and towns in Russia and the Ukraine which went up in flames from the constant attack. The devastation was nearly total. Millions of people had fled their homes, leaving all their possessions behind. The Fuhrer had won a tremendous military success, and by this time almost half of Europe was under his foot. The important powers, England and France, had done nothing to hinder his military advance.

Hitler hoped that the powers would not interfere when his army invaded Russia. In August 1938, upon his return from Moscow with a non-aggression pact, Hitler told his Foreign Minister Ribbentrop, that he had taken care of Russia, and that he had "tricked" Stalin. But Hitler was wrong. The Allied powers joined the war, and eventually defeated Nazi Germany.

Of the groups of young people from Kolomyya who had tried to cross the Russian border by fleeing on foot through fields and forests, few were successful. Only those with vehicles succeeded, and more importantly, only those with firearms, to protect themselves from Ukrainian villagers succeeded.

Hundreds of young Jews in Russian army uniform marched towards the Russian border, together with droves of Jews from Kolomyya and the area. Without guns to protect themselves, they wer brutally murdered by Ukrainians bearing knives and axes. The cruelty of the Ukrainians knew no bounds, even stealing the clothing off the backs of their victims.

Back in Kolomyya, on the night between June 29th and June 30th, 1941, the Red Army took leave of Kolomyya. Before leaving, the Russians destroyed the mail, telegraph and telephone infrastructure, and blew up the train station. They took Ukrainian and Polish prisoners, and set the Jewish prisoners free. The non-Jewish population was infuriated by this last move.

After the Russian evacuation, the Jews remaining in town feared the Ukrainians, known for their hatred of the Jews. The Ukrainians were eager to take revenge on those who had enjoyed good relations with the Communist regime. The Jews boarded up their houses, and tried to protect themselves from a pogrom. It was not long before the Ukrainian mob broke into the deserted Russian camps and stole the weapons and supplies they had left behind. Chaos broke loose, and the marauders began fighting among themselves, as all tried to seize the supplies the Communist regime had left behind.

The Ukrainians lowered the Russian flag above the Town Hall, and replaced it with the independent Ukrainian flag. The mob, armed with Russian guns, wandered through the streets, breaking into Jewish homes and stores. They plundered Jewish property and fired at those who resisted. The rioters advanced, overcoming all obstacles, as fear and dread grew among the Jews. The city was in turmoil, and only a miracle could have saved the Jews from annihilation.

Temporary salvation came in the form of the Hungarian Army. They invaded Kolomyya and the surrounding area within 24 hours of the Russian evacuation. Soldiers filled the city, took up the central positions and proclaimed the imposition of Hungarian military rule. The anarchy in the city ceased, and p. 81 the Ukrainians, who had intended to assist the Nazis in annihilating the Jewish population, were unable to continue with their diabolic plans. The Hungarian army stayed in the city as an ally of the Nazi authorities until the end of 1941, awarding the Jews a few months peaceful respite, until the Hungarians left Kolomyya. Once the Hungarians left, the Gestapo moved in, implementing horrific acts which few survived.